Concorde: How the Plane of the Future Became a Thing of the Past

Or: the rise… and rise, and rise (keep going) and eventual fall of the world’s only successful supersonic airliner.

Screaming down the runway at 250 miles per hour, Concorde was powerless to abort its takeoff. Seconds earlier, a 17-inch strip of metal debris had violently punctured one of its tires, launching a ten-pound chunk of rubber at the underside of its left wing at an estimated 310 miles per hour. The shockwaves from the impact ruptured a fuel tank and kerosene began pouring out, creating a hellish column of orange and black flame that trailed behind the aircraft for hundreds of feet. Air France Flight 4590 took off for the last time.

Both engines on its left side surged and lost power, although one quickly recovered. The landing gear, damaged by the debris, was unable to retract. Lack of thrust from the hampered engines and additional drag created by the extended landing gear made it impossible for Concorde to climb or accelerate. The raging fire began to melt part of its left wing.

The only working left-side engine lost power again, and Concorde banked over 100 degrees to its left as the right wing lifted from the asymmetrical thrust. In an attempt to level the aircraft, the flight crew reduced power to the right-side engines, but the deceleration caused the plane to stall. Concorde slumped to the ground, crashing into the Hôtelissimo Les Relais Bleus. All 109 people on board were killed, as well as four in the hotel, with another six on the ground suffering injuries. The entire flight lasted less than two minutes.

The image of the disaster, perhaps the most recognizable and certainly the most tragic in Concorde’s history, is forever emblazoned in the collective cultural memory of the ill-fated aircraft.

Air France and British Airways both grounded their Concordes after the crash, and although they’d soon return to the skies with enhanced safety features, it would not be long before Concorde was retired for good.

Before the tragedy of Flight 4590, Concorde had been arguably the safest plane in commercial aviation, with a nearly three-decade record in the skies with zero fatalities and only a handful of nonfatal accidents. But since November 26, 2003, no commercial airliner has flown in supersonic service.

So what happened?

“E” for extravagance

The name “Concorde” was first suggested by the 18-year-old son of a publicity manager on the British development team. Meaning agreement, harmony, or union, the name, of course, comes from the word “concord” (or concorde in French) and was chosen to reflect the cooperation between the British and French governments as they turned Concorde from an idea to an ideal.

But this is still the British and French we’re talking about – two countries whose long and complex bond has, at times, more closely resembled a sibling rivalry than a diplomatic relationship. A French author once aptly described the British as “our most dear enemies,” so it was inevitable that even with a project as geared towards collaboration as Concorde, there was going to be a little bit of discord.

And where else should we start, but with a matter so insignificant as the spelling of Concorde? French president Charles de Gaulle first publicly coined the name at a 1963 press conference, but British PM Harold Macmillan opted to drop the E later that year out of frustration at a perceived slight by le président. (De Gaulle, visiting London, said he had a cold and couldn’t see the prime minister. History may never know the truth.)

But the French spelling would be restored yet – the Brits’ technology minister, Tony Benn, announced at a ceremony in France that the spelling would revert to Concorde, insisting that the E stood for “excellence, for England, for Europe and for the entente cordiale,” later stating, “and I might have added 'e' for extravagance and 'e' for escalation as well!” Tony took a real “better to beg forgiveness than to ask permission” approach to this decision, revealing decades later: “I didn't tell anybody I was planning to do it, but once I had announced it in Toulouse, they couldn't do anything about it.” Cheers, Tony.

Before Britain and France joined forces, though, the two countries were each working on their own projects to develop a supersonic transport, or SST. British researchers started exploring the possibility in the 1950s, not long after Chuck Yeager became the first pilot to break the sound barrier in 1947. Previous research had shown that drag at supersonic speeds was strongly related to the length of the wingspan, which led to the use of short, thin trapezoidal wings, not unlike those seen on many missiles or aircraft like the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter.

However, these short wings had trouble generating lift at low speeds, which necessitated longer take-off runs and high landing velocities. This was doable in a fighter jet, but the same design in a supersonic airliner would have required enormous engine power at standard runway lengths and larger airplanes to accommodate all the fuel needed.

One way around this issue is the use of variable-geometry wings, or “swing wings.” These wings can be modified during flight to either be straight or swept, as seen below.

Straight wings are better for takeoff, landing, and efficiency at subsonic speeds, while swept wings are better at supersonic speeds. However, the swinging mechanism is heavy, expensive, and adds a lot of complexity (and associated maintenance needs), so swing wings were a no-go for the British SST project.

Given all these limitations, the researchers decided that commercial supersonic air travel was still infeasible, and they recommended that future research focus on better understanding supersonic aerodynamics.

The story might have ended there, but for two German engineers whose contributions would change the field of supersonic aerodynamics forever: Johanna Weber and Dietrich Küchemann. Johanna and Dietrich were recruited to come to the UK through Operation Surgeon (the UK equivalent of Operation Paperclip, the controversial U.S. program that recruited over 1,600 German scientists to work for the U.S. government, regardless of their Nazi affiliation). (Also, don’t worry, I checked and neither Johanna nor Dietrich were Nazis.)

Their research demonstrated that a “slender delta” wing design (see below) with a high angle of attack (also see below – basically “nose pointed high”) could generate sufficient lift to make takeoff and landing achievable without great difficulty, all without sacrificing the aerodynamic performance at supersonic speeds that would make Concorde so groundbreaking1.

When Dietrich presented the pair’s findings, it was immediately clear that they had overcome the hurdle that previously held back all hopes of developing an SST. Legendary test pilot Eric Brown, who was in the room when the findings were presented, later said he considered this moment to be the birth of the Concorde project.

In all, it took over 5,000 hours of wind tunnel testing and an enormous scientific effort to perfect Concorde’s design. The same principles that define Concorde’s shape have been replicated in essentially all supersonic commercial planes since, so in a sense, Johanna and Dietrich’s work continues to guide the principles of supersonic aviation today.

Parachutes and escape hatches

Meanwhile, France was trying to design its own supersonic airliner. In the late 1950s, the French government requested designs from three different aircraft manufacturers, and the winning design was sent along with a company representative to the UK to discuss a joint Franco-British venture. The British were shocked to discover that the French company’s designs were very similar to their own. Only later would it come to light that one of the original British research reports on SSTs (marked “For UK Eyes Only”) had been secretly shared with the French. Minor changes were made to the report and it was presented as original work. (Nice.)

Rather than signing a commercial agreement, Britain and France entered into the Concorde project under the terms of an international treaty that included a clause requested by the UK government (remember this part) that would impose heavy penalties against either nation for canceling the project. The agreement was signed in late November 1962 with a total estimated cost of £70 million (£1.9 billion in 2025, or about $2.5 billion)

With the project now underway, interest in Concorde began to soar, and orders poured in from airlines all around the globe. Over 100 non-binding commitments were received from operators like Pan Am, Qantas, Japan Airlines, and Lufthansa. Advertisements placed in aviation magazines predicted a market for up to 350 Concordes by 1980.

Spirits must have been high as Concorde looked slated to be a success, but the mood dampened north of the English Channel as the economics of the project soon came into clearer view. Costs ballooned while the UK faced a currency crisis, and British participation in the project started to look less certain.

As it turned out, the cost of collaboration was higher than expected. As Dr. Guillaume De Syon puts it:

Two chains of assembly, two directors, two units of measurement, two of everything (not to mention the need for translators) made the undertaking obscenely expensive from the very start. Engineers doubled as national administrators, effectively negating some of their joint efforts. Even salesmen never compared notes, preferring to focus on where relations with their respective countries were particularly good, to boost their pitch. … In a field where nobody knew how to cooperate internationally, and where organizational charts on both sides of the Channel never quite matched, the supersonic airplane was not the only thing that had to be invented. So did the seamless web, from engineering practices to flight regulations.

Despite publicly supporting the Concorde project, the UK government secretly thought it was a financial disaster in the making and sought to withdraw from the pact they’d signed with France. Our old friend Tony Benn was tasked with “establish[ing] a strategy of withdrawal” in 1968. However, bound by the terms of the treaty (and the cancellation clause they’d requested), there was no way for the Brits to abandon the development without owing France substantial damages and causing themselves great embarrassment. In the end, the UK could not resist the political pressure and was forced to stay on board, eventually seeing the project through to completion.

The first test flight of a Concorde prototype, piloted by André Turcat, took off from Toulouse in March 1969, and the first British-built prototype flew about a month later. Emerging from the cockpit with the eyes of Britain upon him, pilot Brian “Trubby” Trubshaw said, “It was wizard.”

Millions tuned in to see Concorde take flight, and if not for the Moon landing just four months later, it would have been the highest-rated television event of 1969. Viewers enjoyed the display and were thankfully spared from witnessing the worst-case scenario, which the pilots prepared for by wearing parachutes while flying mostly over water in aircraft specially fitted with escape hatches.

Doling out croissants

Following the success of the prototype flights, Concorde staged a promotional tour around the globe. Sixty technicians and salespeople traveled with the planes as they tried to emphasize Concorde’s speed and the convenience it offered. At the same time, they pushed back against worries over its cost, justifying its high price tag by arguing that “no part of its cost was hidden in the military budget.” The New York Times detailed how Concorde “took off into a wild blue yonder of uncertainty” as it set off to Athens, Tokyo, Tehran, and eight other stops along the way.

Concorde visited the U.S. for the first time in 1973 as it christened the soon-opening Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, then “the world's largest jetport,” according to the New York Times. A reporter described “the gentlest of bumps as the plane went through the once mysterious and dreaded sonic barrier” on its way to Texas from Caracas, while British airline officials sought to reassure passengers that “the plane is not the monster many people think it is.” As Concorde surpassed Mach 2 – twice the speed of sound – applause rang out from those onboard for whom this was still a novelty, while a seasoned French flight attendant “did not pause in doling out croissants.”

Riding this wave of hoopla and acclaim, Concorde’s developers surely must have had high hopes for the years ahead, but their predicted success would not be so. By the end of its development and after enduring numerous delays and cost overruns, Concorde’s price tag had jumped to a whopping £1.5–2.1 billion in 1976 (£14–19 billion or $18-25 billion in 2025). At the highest estimate, this would put the total cost at ten times higher than the original estimate.

Unsurprisingly, the airlines were not thrilled about these rapidly escalating costs, and orders began dropping like flies. Lufthansa’s chairman reportedly “yelled at shareholders in the 1970s that he could forecast his company's bankruptcy according to how many of the aircraft it ordered.”

Nearly 40% of all reserved orders for aircraft were cancelled in just the first three months of 1973, and by the end of the year, only 30 orders remained (just 14 of which would ultimately be filled). The chairman of the British Aircraft Corporation put it aptly: “We should not describe this as a fatal blow, but it’s a hell of a setback.”

Air France and British Airways would end up being the only customers for Concorde, in part because, as state-owned airlines of their respective countries, they had no choice but to purchase the aircraft. Billions of dollars of public funds had been sunk into the Concorde project and taxpayers would never come close to seeing a return on their investment. Budgets soared out of control, partially due to inflation and partially due to “man’s unfailing ability to underestimate the costs of advanced technology.”

Things looked bleak for Concorde as it entered service on January 21, 1976. Two flights, operated by Air France and British Airways, took off simultaneously from Paris and London, en route to Brazil and Bahrain, respectively.

One other airline would briefly operate Concorde, although its short run and quick demise would be a harbinger of misfortune to come for the aircraft. In a sharing agreement with British Airways, Singapore Airlines began thrice-weekly flights between London and Singapore in December 1977. The Concorde flying the route was painted in Singapore Airlines livery on its left side but kept its British Airways paint job on the right, in a sort of “Will Forte half beard” look. (Or maybe a mullet? Business Singapore on the front left, party Britain on the back right.)

Almost immediately, noise complaints from the Malaysian government forced Singapore Airlines to find a new route bypassing its neighbor’s airspace, and after an alternate flight path over India was also ruled out, the service was canceled.

The British and French Concordes continued on, undeterred, but the sound barrier wasn’t the only resistance they would run nose-first into.

Hitting some turbulence

Concorde was a needy airplane. For every hour it spent in the air, it required 18 hours of maintenance, and every one of those hours spent on the ground ate into its profit-making potential.

Concorde was a very expensive plane to operate. It burned about 6,700 gallons of fuel per hour, compared to the measly 850 gallons per hour used by the most popular commercial plane today, the Boeing 737. According to a former chief engineer at British Airways, “Concorde used as much fuel taxiing to the end of a runway as a Ryanair-size Boeing 737 flying from London to Amsterdam.” In 1979, the New York Times compared Concorde’s fuel efficiency to that of a Boeing 747, finding that it used four times the amount of fuel to carry less than a quarter of the passengers as the 747 on a flight from New York to Paris.

On top of that, a ticket aboard the Concorde was a big expense. Round-trip tickets in the 1990s could go for as much as an inflation-adjusted $20,000, and despite the sky-high ticket cost, the accommodations inside the cabin left much to be desired. The slim demands of the body’s design meant comparatively cramped interiors for passengers and crew, an issue that only intensified as premium offerings aboard other aircraft improved over the years. While at first, Concorde’s austere environment was in line with what its competitors were selling, it soon found it hard to compete with the cheaper and more luxurious first-class seats on slower airplanes. Towards the end of its tenure in the skies, Concorde was competing with planes that offered lay-flat first-class seats for 15% less than its supersonic fares. The calculus for passengers started to change as the few hours of time saved aboard Concorde looked less appealing compared to the more comfortable experience they could have lying down on a subsonic craft.

Contributing to this high ticket price was the soaring cost of oil during the 1970s, coupled with Concorde’s astoundingly poor fuel efficiency. Concorde achieved 15.8 passenger miles per gallon (assuming a sold-out plane, which is a bad assumption to make with Concorde), compared to competitors that could reach as high as 53.6 passenger miles per gallon. This higher per-passenger fuel use not only drove up ticket prices, but also tied them more closely to the market fluctuations of oil prices.

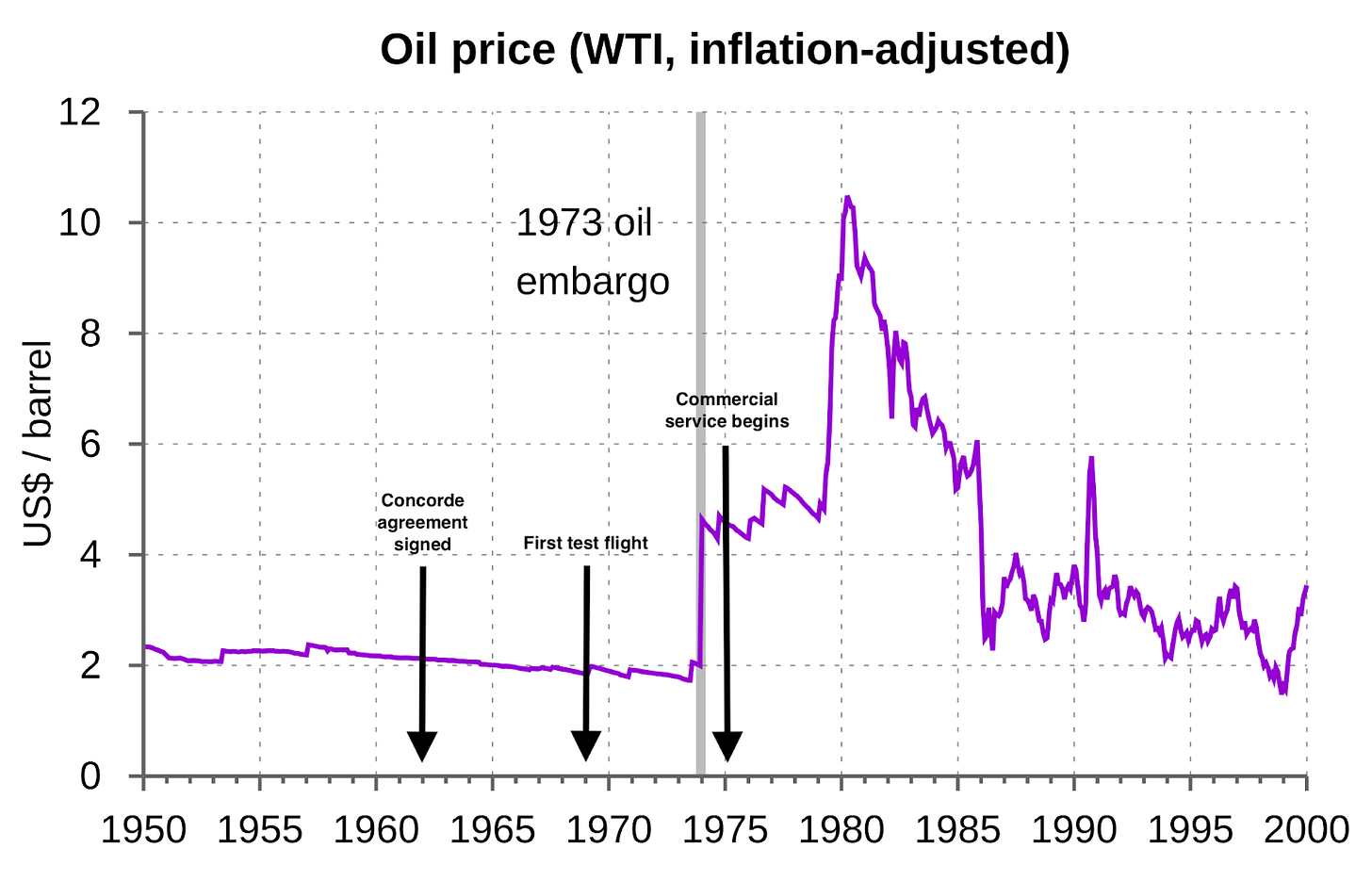

Concorde’s designers knew it would be a gas-guzzler when they built the plane, but they were banking on the promise that it’d outpace the competition owing to its superb efficiency at supersonic speeds. However, they were unable to foresee the turmoil caused by the 1973 oil embargo. This is what bad luck looks like:

This was a very unwelcome development for the operators of an aircraft that consumed about one ton of jet fuel per passenger.

Concorde’s heavy fuel use, combined with the limited space for fuel storage onboard, also limited its range to 4,500 miles, preventing it from serving routes like Los Angeles to Tokyo or Sydney to Beijing. These challenging market realities forced Air France and British Airways to scale back the already-limited route offerings for Concorde, eliminating destinations like Miami, Singapore, and Rio de Janeiro. A vast majority of flights taken during Concorde’s three-decade tenure were limited to two routes – New York to London and New York to Paris.

High fuel use was not only a concern for the airlines’ pocketbooks, but also for their public relations departments. Continuing with its streak of bad luck, the fuel-thirsty Concorde ran into the headwinds of a burgeoning environmental movement that sought to curtail the creation of pollution. Here’s a quick timeline to put into context how inauspicious Concorde’s timing was:

March 2, 1969: first Concorde test flight

April 22, 1970: Earth Day celebrated for the first time

December 2, 1970: Environmental Protection Agency established

1971: Greenpeace founded

1972: UN Environment Program Founded

January 21, 1976: Concorde enters commercial service

While lower-flying subsonic airliners also create pollution, Concorde spewing its sulfur-laden exhaust at twice the elevation was thought to contribute more quickly to the degradation of the ozone layer. And while the small fleet of only 14 Concordes meant the overall environmental impact was comparatively negligible, it was theorized that a fleet of 500 SSTs “could persistently produce enough particles to equal the levels seen after small volcanic eruptions.” This kind of pollution could potentially cause a 2% reduction in global ozone levels and contribute to a 4% increase in non-melanoma skin cancer rates worldwide.

Beyond the impact on the natural environment, Concorde opponents were also concerned about its tremendous effect on the acoustic environment in the vicinity of its flight path.

From the beginning, Concorde attracted protests from those who could not ignore its newfound presence in the skies. Starting in 1976, Long Island residents crowded the areas around John F. Kennedy International Airport, clogging the roads with hundreds or thousands of cars driving as slow as five miles per hour. Despite insisting that demonstrations were orderly, one organizer threatened that 10 to 20 people could “close the airport if they dropped sand from trucks or overturned cars.”

Protestors demonstrated their proficiency in the art of sign-making:

“Boston Had a Tea Party, JFK Has an SST Party,” one crayoned sign proclaimed. “1775 First Battle of Concord. 1976 Second Battle of Concorde,” another declared in the effort to set up a noise that could be heard around the world—or at least, it was hoped, in Albany.

And one onlooker made an observation with comedic timing straight out of a sitcom:

Bracing against the sustained noise from the horn‐blowing, a Port Authority policeman eyed the fumes from exhausts of the idling and stopped cars in the motorcade and observed, “I thought they were against pollution.”

The protests would prove their effectiveness. On March 11, 1976, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey banned Concorde from landing at JFK, angering the airlines and setting up a consequential legal fight. British Airways and Air France found the ban baseless and sued to overturn it, but local residents were pleased: “We won't have the noise aggravation. Plus, the French are losing money.” Amen, brother.

As protests continued into 1977, the New York Supreme Court issued an injunction ordering protestors not to “plan to clog or tie up” the areas around JFK – an order which was summarily ignored. Protests continued as airport workers and airline staff had their scheduled time off canceled and were told to come in early to get ahead of disruptions. Police came prepared with additional officers and had tow trucks at the ready for any vehicles that refused to move.

In August 1977, a district court judge found the ban to be “discriminatory and unfair” and allowed Concorde to conduct test landings at JFK. The ban was formally lifted by the U.S. Supreme Court two months later. Justices ruled that the Port Authority was “dragging its feet” and had not based the ban on any specific noise requirements, warning that innovation was "in imminent danger of being studied into obsolescence."

I had an unusually difficult time finding solid sources attesting to the exact decibel levels of Concorde taking off and landing, but many assert that Concorde was noticeably louder, owing to its more powerful engines and use of afterburners to help get it off the ground. In October 1977, the New York Times documented Concorde coming in below the legal noise limit during its first-ever takeoff from JFK and noted that it was not much louder than the subsonic jets that had taken off directly before and after it. Apparently, Concorde was even quieter than some subsonic jets when it came in for landing. However, opponents insisted that Concorde was twice as loud as the loudest subsonic planes. They claimed that while subsonic aircraft produced around 95 decibels of noise at takeoff (hairdryer, approaching subway train, crowing rooster), Concorde could reach nearly 120 decibels (thunder, concert, nearby sirens).

As someone who lives in the flight path of a busy airport, I can personally vouch for the fact that you can easily tell by noise alone when the plane flying overhead is more powerful. The intensity of the sound instantly tells you whether it is a 737 or a 747, and whether the flight is more likely headed off to Seattle or Seoul, so I don’t doubt for a second that Concorde was noticeably noisier and more disruptive.

Even our friend from earlier, British technology minister Tony Benn, admitted that the noise was astounding — “when … it boomed into the air, the vibration was so great, I felt I was being filleted; as if the flesh was falling off my backbone.”

And while there was indeed great concern over the noise at takeoff and landing, it paled in comparison to the discontent that arose from the sonic boom. But before we get into that, let’s make sure we’re all on the same page as far as how sonic booms work.

Just a little bang

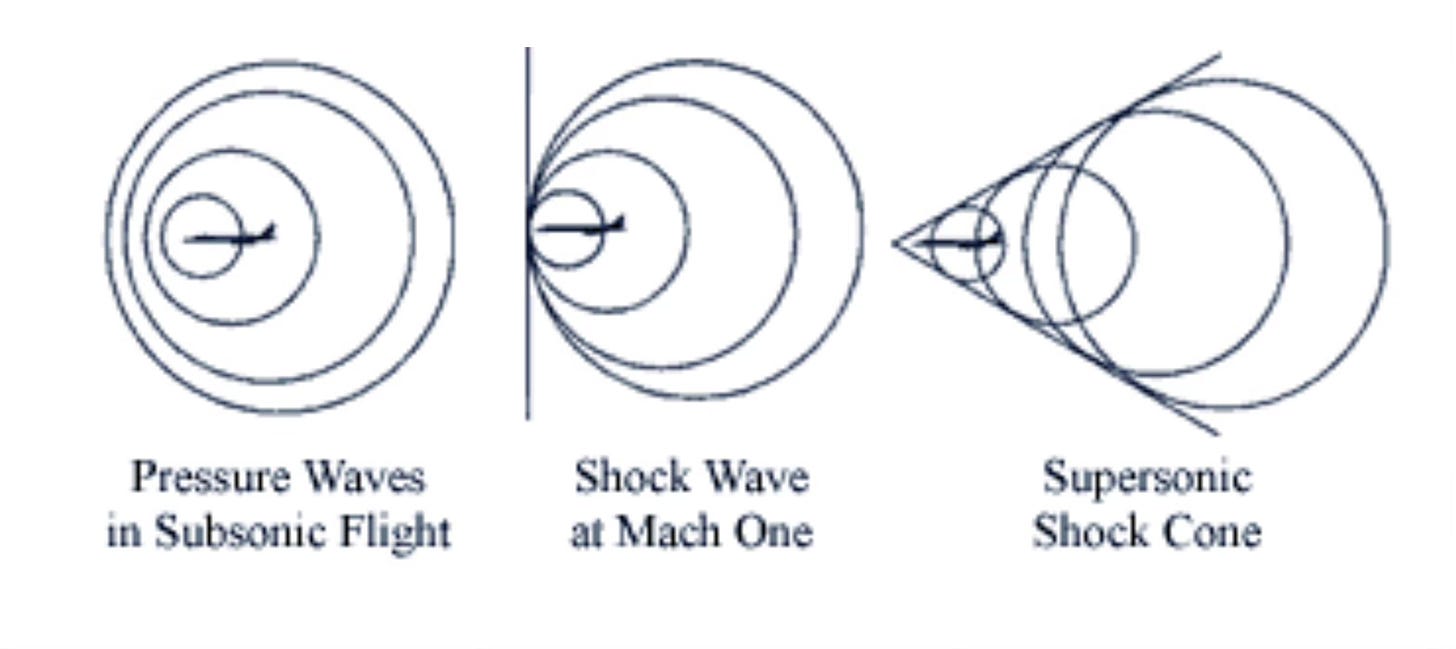

When a plane (or any object) travels through the air, it creates pressure waves, in the same way that a boat traveling through water creates waves. These waves radiate out from all around it, and as a plane goes faster, it begins to essentially catch up to the waves that it is producing. When a plane exceeds the speed of sound, it breaks the sound barrier and begins to outpace its own pressure waves, causing them to compress and form a shockwave that is heard as a loud, thunder-like noise on the ground. In fact, the sound of thunder is actually a sonic boom itself, caused by “the rapid expansion of super heated air caused by the extremely high temperature of lightning,” according to the NOAA.

A common misconception is that a sonic boom is produced only once, at the moment an object breaks the sound barrier, but it is in fact constantly producing a sonic boom for as long as it is traveling faster than sound. Thus, although individual observers on the ground may only hear it as a single, isolated boom, the sound is continuously roaring across the landscape, trailing slightly behind its source.

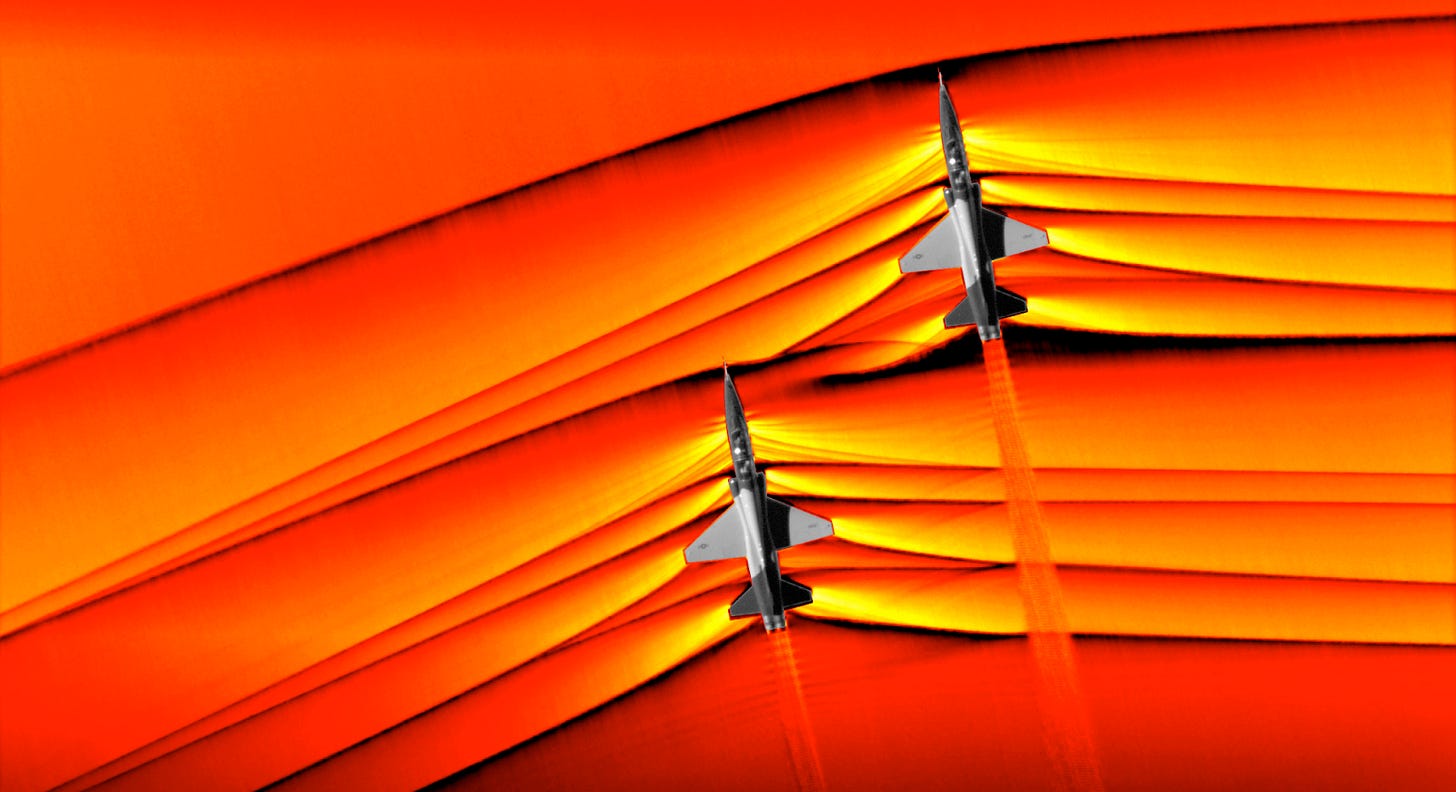

The below image is not an artwork – it is a real (colorized) photograph of shock waves interacting between two supersonic aircraft, just 30 feet apart from each other, taken by NASA in 2019 using a method called Schlieren photography. This process allows scientists to photograph the flow of air around objects. I won’t embarrass myself by attempting to explain the science behind this, so here’s Wikipedia: “The process works by imaging the deflections of light rays that are refracted by a moving fluid, allowing normally unobservable changes in a fluid's refractive index to be seen.”

Please watch this unexpectedly ASMR-inducing video from a Harvard lab to learn more, and find even more information here if you’re interested.

Anyway, sonic booms – they were controversial! Concorde proponents sought to downplay the disruption caused when the sound barrier was pierced. Here’s Tony Benn again:

There had also been a great anxiety about the sonic boom that Concorde would create, so I had said to Harold Wilson, I'm going to arrange for a supersonic bomber to overfly Whitehall and create a sonic boom at midday while the cabinet is meeting. I didn't tell anybody else. When we heard the boom overhead, Miss Nunn, the secretary to the cabinet, was a bit shaken and said, "What was that?" and I said, "Oh, that was just a sonic boom." They had imagined it would be like Vesuvius erupting, when it was just a little bang.

Side note: I know nothing else about Tony Benn, but I love how often his decision-making seems to be guided by “I’m just gonna do this thing and not tell anybody beforehand, what are they gonna do about it?”

Despite Tony’s comfort with the boom, though, others were less assuaged and had many lingering concerns about noise pollution. It had been thought that the sonic boom could be minimized by simply flying higher, but noise remained an issue even as high as 70,000 feet (as demonstrated by XB-70 Valkyrie test flights).

Governments sought to measure the impact and public perception of sonic booms by civilian populations, but crucially, and perhaps regrettably, did not begin studying this until after the Concorde project was already well underway.

In the early 1960s, the U.S. government conducted 150 supersonic test flights over St. Louis, Missouri, in what was for some reason called “Operation Bongo.” Air Force pilots repeatedly flew B-58 bombers over the city for ten months, dropping thunderous booms each time. The government later concluded, quite clinically, that “some reaction may be expected” from citizens, while an Air Force major put it more bluntly to The New Yorker, saying sonic booms were a “top-priority public-relations problem.”

In 1967, the UK’s Ministry of Technology (led by Tony Benn) flew 11 supersonic test flights over the south of England, finding that “[n]early two thirds of the population of Bristol were frightened, startled or annoyed.”

And in what is probably my favorite story of the entire Concorde saga, the U.S. government came roaring back in 1964 with Operation Bongo II (Electric Boogaloo), organized by the FAA. This time, St. Louis was spared, but the government instead set its sights on Oklahoma City. Over the course of six months, sonic booms would be generated over the city eight times a day for a grand total of 1,253 sonic booms.

The FAA began conducting flights without seeking permission from Oklahoma City’s elected officials. Most residents went along with it at first, partially because Oklahoma City’s economic fate was so closely tied to that of the aviation industry. Indeed, one out of every six residents worked in aviation, many for the FAA and the Air Force, which had a major base nearby.

People saw it as their “patriotic duty” not to complain while the government conducted its purportedly important work at their expense. But as the experiment progressed, the booms got more intense and residents began to grow weary of their continued presence in Oklahoma City’s skies.

Local organizers started agitating for city leaders to do something, but they got the cold shoulder and an entreaty to please be supportive, the government is very busy tormenting you. After a sustained effort and increased national attention to the matter, though, Oklahoma City politicians finally relented and began an (ultimately unsuccessful) legal battle to end the booms. Soon after, the FAA discontinued the tests on its own accord, abruptly bringing to an end one of the most bizarre sagas in the history of American aviation.

After the discouraging misadventures of the Oklahoma City sonic boom tests, the FAA opted in 1973 to ban overland supersonic commercial flight, a ban which is still in effect today. Numerous other countries also prohibited the practice, which severely limited the range of possible routes for Concorde. Supersonic flight would only be permitted over open ocean, so any routes that spent too much time traveling over land would now be infeasible, given Concorde’s stark inefficiencies at speeds below the sound barrier.

A plane with a lot of baggage

But despite all these issues — design challenges, bi-national tensions, skyrocketing development budgets, hemorrhaging orders, pricey operational costs, limited route availability, the 1973 oil crisis, environmental concerns, noise troubles at every stage of flight, and more – Concorde still managed to have a semi-successful near-three decade run in the skies, and remains one of the most iconic aircraft.

Quite simply, Concorde was a masterpiece of engineering and a monument to human ingenuity. It overcame seemingly insurmountable hurdles at every stage of its development and served as a star-studded limousine in the skies for an entire generation. Its speed and glamour mesmerized (and continue to mesmerize) millions, and it lingers in the shadows of our collective cultural memory like an ex that we just can’t get over.

Aboard Concorde, passengers could peer out the windows and observe the curvature of the Earth as they raced along faster than its rotation. They could witness the glowing blue rim of the atmosphere radiating off the Earth’s surface like the glow of a TV screen, gradually fading into dusky purple and impenetrable black.

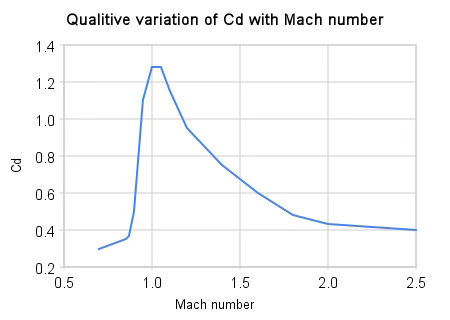

As the plane grew faster, it would encounter a powerful force called wave drag, where “[s]hock waves form due to the air being unable to ‘get out of the way’ quickly enough.” This created a considerable amount of drag and required the use of afterburners to overcome, producing a sensation that was felt onboard “like a fast sports car dropping a gear.”

At 60,000 feet, the outside air temperature was -67°F / -55°C, but the skin of the aircraft could get as high as 260°F / 126°C from kinetic heating, causing windows to be hot to the touch. The fuselage slowly expanded as it heated up, growing as much as a foot and creating gaps in between flight instrument panels. It’s said that during the Concorde test program, a flight engineer tucked his hat into one of these gaps but found he could not remove it after the plane had landed, as the airframe had cooled and the gap had closed.

To counteract overheating, Concorde’s surface was primarily painted with anti-flash white, a highly reflective white color also used on nuclear bombers to reflect thermal radiation.

Speaking of which, the higher cruising altitude of Concorde meant its passengers received ionizing radiation at almost twice the rate as passengers on similar subsonic flights, but the substantially shorter flight time meant the overall dose would generally be lower. Concorde’s flight crew also had to monitor radiation levels in case of unusual solar activity, in which case they would descend below 47,000 feet.

The higher altitude also meant greater danger in the case of cabin depressurization. At Concorde’s cruising altitude of 60,000 feet, the time of useful consciousness (the amount of time a person is able to perform flight duties) is less than 15 seconds, even for a conditioned athlete. A sudden breach of cabin integrity would result in such a severe loss of pressure that emergency oxygen masks would be useless and passengers would quickly suffer from hypoxia. Concorde’s windows were made noticeably smaller (about the size of a hand) to slow cabin depressurization if a breach occurred, in which case a rapid descent by the pilots would bring the plane down to a safe altitude.

So long as the cabin did not depressurize, the experience aboard Concorde was stellar and second-to-none. In 27 years, over 1 million bottles of champagne were consumed onboard, often enjoyed alongside extravagant multi-course meals. Concorde’s chefs went all out for the final flight, serving “Scottish smoked salmon and caviar, vintage Champagnes, lamb cutlets, beef fillets, lobster fishcakes, a truffle omelette, and a buttermilk panna cotta dessert.” Surely, if Jerry Seinfeld had flown on Concorde, he’d have never complained about airplane food.

These luxuries made Concorde the plane of choice for the rich and famous who wished to zip across the Atlantic in style. It was a status symbol just as much as it was a mode of transportation. Passengers included, but were certainly not limited to, Paul McCartney, Elizabeth Taylor, Queen Elizabeth II, and Pope John Paul II.

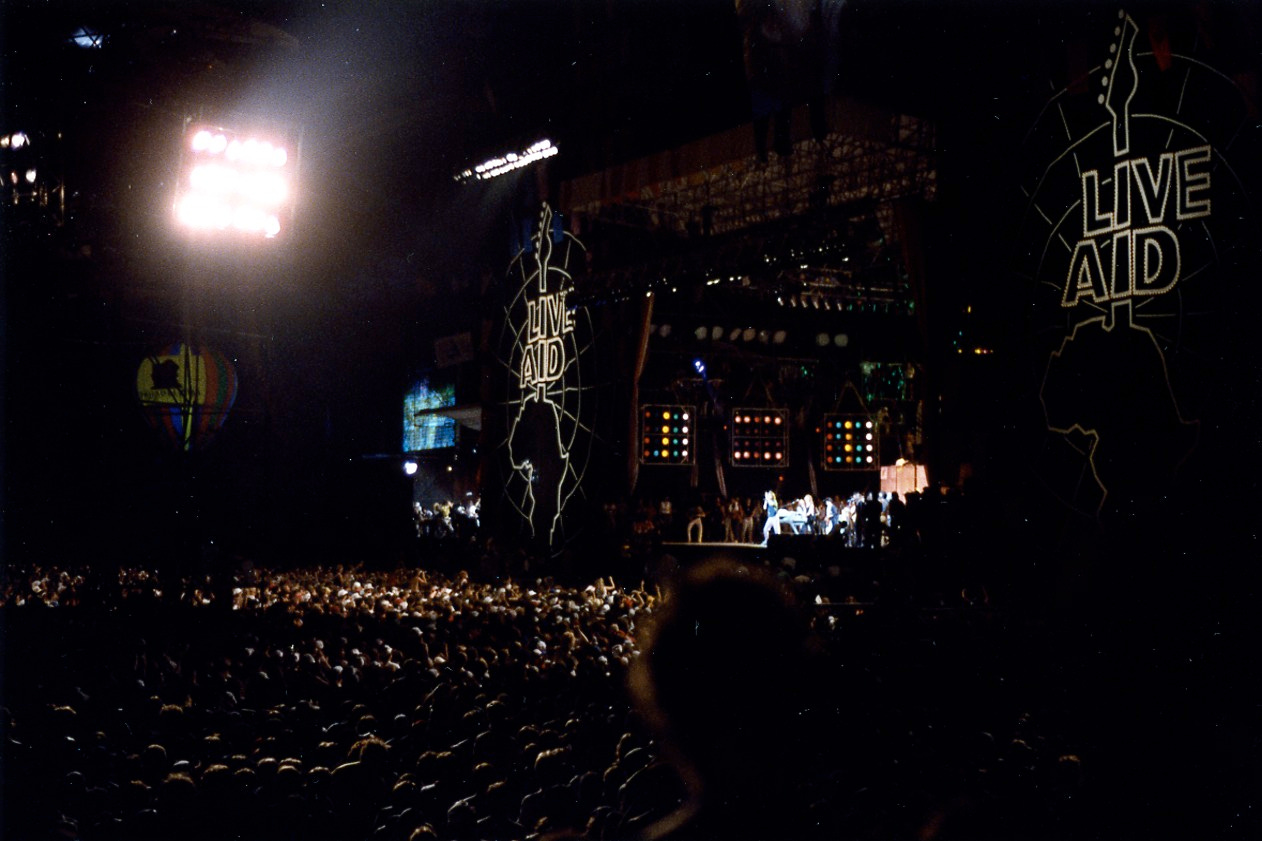

In 1985, Phil Collins used Concorde to make music history, playing Live Aid at London’s Wembley Stadium, taking a helicopter from Wembley to Heathrow, jetting over to JFK, and taking another helicopter to Philadelphia to also play the Live Aid concert there. While aboard Concorde, he ran into Cher, who was unaware of Live Aid. You know – the Live Aid that had an estimated television audience of 1.9 billion people, nearly 40% of the global population – yeah, that Live Aid. Cher just… didn’t know about it. I swear I’m not trying to be mean to Cher – I’m just so puzzled as to how she simply did not know it was going on.

As Phil later recounted, when he first encountered her, “she didn’t really look like Cher,” clarifying that she had “house clothes” on. Phil shared my disbelief with Cher’s blind spot for Live Aid, saying, “If you haven’t read about it, I don’t know where you’ve been.”

But he was happy to share with Cher: “I told her about Live Aid and she asked whether I could get her on. I told her to just turn up.” Cher, clearly on board with this plan, “went to the bathroom, came back looking like CHER!” (Phil did an excited gesture while recalling this moment.)

“I landed in New York, said my goodbyes to Cher and headed to the stadium in Philadelphia.”

But the hectic day split between time zones would catch up to Phil, and by the time he finished his set in Philadelphia “it just felt like 5am to me.” Exhausted, Phil retired to his hotel room and got there just in time to catch Live Aid’s grand finale on TV. “Everyone came on to sing 'We Are the World' and there, at the back, was Cher, singing along. She'd just turned up!”

Born from dreams

When Concorde wasn’t whisking Cher to unplanned ensemble performances, it was carrying elite business travelers across the ocean to meetings that presumably could not have been emails. After struggling to make a profit for its first six years of operation, British Airways conducted market research that showed many regular passengers, mostly business travelers, had no idea how much a ticket should cost. These VIPs had assistants to book their tickets for them, so they assumed tickets cost more than they actually did. Rather than devising a marketing campaign to convince people of Concorde’s lower-than-anticipated costs, airline executives simply raised prices to be in line with what people thought they were paying anyway. British Airways’ Concorde fleet started making a profit shortly thereafter.

Bucking conventional wisdom, Concorde’s operators stopped trying to make its fares affordable and instead repositioned itself as a luxury travel affair. A trip aboard Concorde became an elevated experience in more ways than one (sorry). Once they identified Concorde’s appeal to those for whom time was infinitely more valuable than money, and for whom money was no object, they really started seeing success.

This is perfectly illustrated by a Smithsonian curator’s experience aboard a Concorde retirement flight in June 2003. Seated next to a former president of Air France, he was served caviar and champagne, but soon learned what a faux pas this was: “Girandet explained to me in broken English that it was just unthinkable to serve champagne with caviar. What did I know? I’m a middle-class civil servant from the suburbs. Apparently, caviar should only be accompanied by vodka. I’ll remember that next time.”

To commemorate their experience onboard, British Airways would issue passengers certificates affirming that they’d broken the sound barrier during their travels, in another of the countless ways that Concorde made the extraordinary feel routine. Its tagline, “Arrive Before You Leave,” captured the allure and excellence that drew so many to its impressive frame that could traverse the distance between London and New York in as little as 2 hours, 52 minutes, and 59 seconds, a commercial speed record that still stands today.

In all, British Airways’ Concorde fleet recorded more than 140,000 flying hours across nearly 50,000 flights and traveled 140 million miles while carrying 2.5 million passengers. More people flew aboard the Space Shuttle than piloted the Concorde in its 27 years of service.

But all that Concorde had done to cement its image of excellence and prestige would vanish in an instant on July 25, 2000. In a manner entirely uncharacteristic of the aircraft known for its elegance and speed, Concorde went down in a slow, ugly collapse, culminating in a massive fireball that claimed the lives of 113 people.

It was a devastating blow from which Concorde would never recover, and the result of a cursed coalescence of bad luck working counter to Concorde’s fortunes.

Flight 4590’s takeoff was delayed by 66 minutes that afternoon due to last-minute repairs that the captain insisted upon despite being deemed nonessential to the aircraft’s safety. No spare parts were immediately available to fix a defect with the thrust reversers in one of the engines, but Captain Christian Marty refused to leave the gate until the repair was completed with a replacement part taken from a reserve Concorde stored at Charles de Gaulle Airport. Once complete, Flight 4590 taxied to the runway and took off five minutes after Continental Airlines Flight 55, which dropped the piece of metal debris that would doom Concorde.

In a cruel twist of fate, Captain Marty’s insistence on the repair and his refusal to take any chances with the safety of his airplane is precisely what put Flight 4590 in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Furthermore, Concorde only reached its V1 speed – the point of no return during takeoff – seconds before it struck the metal debris. At that point, there was no turning back, and any attempt at aborting the landing would have certainly resulted in numerous casualties as well.

As Flight 4590 sped down the runway with air traffic control alerting the crew, “You have flames behind you,” France’s president, Jacques Chirac, helplessly watched the events unfold from the window of a Boeing 747 which had just landed after returning him from a G8 summit in Japan. The damaged Concorde veered to the left as it continued down the runway, coming within 30 feet of Chirac and the other passengers aboard the plane.

After the crash, Air France grounded their Concordes immediately. British Airways paused Concorde flights for a few days but resumed operations with enhanced safety and maintenance procedures shortly thereafter. This lasted for a few weeks until the Civil Aviation Authority (the UK equivalent of the FAA) forced British Airways to cease operations pending a full safety review. According to National Geographic, “This came into such sudden effect that a Concorde flight to New York had to cease its taxi and return to the terminal.”

Burst-resistant tires, Kevlar-lined fuel tanks, and more secure electrical controls were added to Concorde to prevent future catastrophes, and within a year, flights with passengers were restarted. The first flight was not a commercial flight and carried only British Airways employees on a brief test flight departing from and returning to Heathrow Airport. Upon completion of the flight, British Airways would conduct a briefing to share the safety improvements they’d made to prepare Concorde for its return to service. The flight took off from Heathrow on the morning of September 11, 2001.

Back at Heathrow, journalists awaiting Concorde’s arrival began hearing reports of the attacks unfolding in New York. They anxiously watched on television as thick smoke rose from the North Tower, with Concorde still obliviously in the air. Soon after, the test flight landed and Concorde’s chief pilot entered the room, taking a brief glance at the TV and remarking, “Oh, that looks horrific,” and then, “Now we switch off the TV and turn to Concorde2.”

Two months later, fare-paying passengers returned to 60,000 feet aboard Concorde, but the aircraft was flying on borrowed time. It would only limp along until April 2003 when Air France and British Airways announced its impending retirement later that year. The reasons were numerous and unsurprising – dampened passenger interest in flying Concorde after the crash, a general downturn in air travel following 9/11, and rising maintenance costs after Airbus, Concorde’s manufacturer, decided it would no longer supply replacement parts for the aircraft.

Concorde had become an aircraft simultaneously futuristic and outdated. It no longer made economic sense to continue operating the plane, which was reportedly flying at only 20% capacity on Air France and was suspected to be a loss leader for the airline. British Airways, on the other hand, made a net profit of £500 million (nearly $650 million) over its lifetime and was still making money in its final few months, according to Jock Lowe, Concorde’s longest-serving pilot. But tellingly, British Airways revealed that retiring the fleet “would result in £84m write-off costs for the year ended March 2003.” As one NPR commentator put it, “Commercial supersonic flight will become like travel to the moon: a goal achieved, and then long abandoned.”

Ultimately, Concorde’s downfall came also as a result of its inability to keep up with the times. Owing to its necessarily narrow fuselage, it couldn’t adapt to the increasingly high demands of the luxury air travel market, leaving its speed – once the defining characteristic that set it apart from the competition – as its sole amenity, and one which was wholly insufficient to keep up with the crowd. As The Guardian’s Dave Hall put it: “Concorde was an outdated notion of prestige that left sheer speed the only luxury of supersonic travel.”

It was a sad end to a brilliant career in the skies, and one which may always be remembered for what could have been. As pilot Mike Bannister recalled: “I remember after the very last flight there was a reception at BA. I was last to leave, it was foggy outside and there were five perfectly serviceable Concordes all sitting there under neon lights, and I have to admit there was a tear in my eye.”

In the end, Concorde is prized as much for the technical innovations it ushered in and the practical advantages it offered as for the indelible cultural impact it left behind, and the way it showed us that the impossible could be achievable.

Concorde’s final flight came on November 26, 2003, departing Heathrow for the last time en route to Bristol, where it is today showcased at an aerospace museum. Its final commercial flight was a month earlier, departing New York’s JFK for London. So abundant was the fondness for Concorde that grandstands seating over 1,000 were erected at Heathrow and authorities had to urge people to stay away, culminating in the Telegraph headline: “Chaos fear at Concorde farewell.”

Mike Bannister was at the helm as Concorde made its final landing at Heathrow, declaring to his passengers after touching down, "Concorde was born from dreams, built with vision and operated with pride. Concorde has become a legend today. Thank you for joining us for a moment of history.”

When he first started training to fly Concorde in 1977, Bannister was the youngest person to ever pilot the craft. But as Concorde now neared its retirement, so too did he, with his 55th birthday approaching and his time as chief Concorde pilot for British Airways coming to an end.

"Looking back at the entire program, from beginning to end, if you knew then what you know now, then Concorde would never have been built," Bannister said.

Another Concorde piloted by Bannister, this one destined for Seattle’s Museum of Flight, blistered across Canada’s skies in early November 2003. It traversed in just under four hours a distance that normally takes more than six, achieving an hour and a half of supersonic flight in a sparsely populated corridor after gaining special permission from the Canadian government.

One last time, this Concorde heated up to over 200 degrees Fahrenheit. One last time, its fuselage expanded by over a foot. And one last time, a gap opened between the flight instrument panels.

Like so many others before him had done, flight engineer Trevor Norcott wedged his cap in the space between the panels. But this time, instead of removing it before it became stuck, he left it there. As the plane descended towards Seattle, its skin began to cool and its fuselage began to shrink, trapping the cap in the body of Concorde forever.

Gods, sky voyaging

Concorde will never return to our skies. We may see another supersonic airliner yet, but it will bear a different name, a different livery, and a different shape (but not too different). For now, though, the dream of faster-than-sound commercial flight is dead. Humanity, as in the myth of Icarus, flew too close to the Sun.

The great Roman poet Ovid, in his magnum opus the Metamorphoses, writes from the perspective of Daedalus, father of the fallen Icarus:

“My son, I caution you to keep

the middle way, for if your pinions dip

too low the waters may impede your flight;

and if they soar too high the sun may scorch them.

Fly midway. Gaze not at the boundless sky,

far Ursa Major and Bootes next.

Nor on Orion with his flashing brand,

but follow my safe guidance.”

Be honest — if your dad built you a pair of wings and told you not to gaze into the boundless sky, where do you’d gaze and why would it be the boundless sky? I mean, c’mon, were you ever really going to be able to resist? What was Daedalus thinking? “Gaze not at the boundless sky” sounds like exactly the sort of thing a person would say if they were trying really hard to get somebody to gaze directly at the boundless sky. You can’t just describe the sky like that and expect me not to gaze at it.

Anyway, after Icarus fell into the sea and drowned, Daedalus went to the temple of Apollo in Sicily and surrendered his own wings as an offering to that god of Sun and light, of truth and prophecy. Daedalus vowed he would never attempt to fly again.

Ovid’s contemporary, Virgil, related in his masterpiece, the Aeneid, the experience of those watching the fateful flight from the ground:

A fisherman, who with his pliant rod

was angling there below, caught sight of them;

and then a shepherd leaning on his staff

and, too, a peasant leaning on his plow

saw them and were dismayed: they thought that these

must surely be some gods, sky-voyaging.

Even with failure, sometimes catastrophic, still not too distant in humanity’s collective rearview mirror, we strive today for the upper reaches of the sky once again. Since Concorde’s final flight in November 2003, no less than a dozen projects have been undertaken that hope to replicate, if not exceed, the feats that Concorde achieved in its heyday. We may well see supersonic commercial flight return before the decade is through, or at least test flights to demonstrate its feasibility, perhaps to provide a measure of reassurance (to whom — the public, investors, the people of Oklahoma City?).

Because while some see Concorde’s story as one of failure and hubris, others see it as one of triumph and tenacity. Not a cautionary tale or cause for a sacrificial hanging-up of the wings, but a dare to come back and try again, to do better next time. In the end, after all, Concorde made a profit, and that may be the only necessary prerequisite to get the industry back on board with SSTs, no matter the havoc they may or may not wreak on our environment and no matter the thunderous disruption their sonic booms may involuntarily foist upon unsuspecting Oklahomans.

Indeed, Icarus, like Concorde, did not fail, says the poet Jack Gilbert in his Failing and Flying:

Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew.

It’s the same when love comes to an end,

or the marriage fails and people say

they knew it was a mistake, that everybody

said it would never work. That she was

old enough to know better. But anything

worth doing is worth doing badly.

Concorde took to the skies as a beautiful “white bird,” admired by so many for its engineering brilliance and aesthetic elegance eleven miles above the surface of the Earth. Then, it became a white elephant, a heavy financial chain around the necks of Air France and British Airways, an environmental and acoustic blight, and, at times, a public relations nightmare. And finally, today, it has become something of a white whale, an irrational, misguided vision of a dream that we aspire towards anyway. As Captain Ahab said, “All my means are sane, my motive and my object mad.”

Is our dogged, still-ongoing pursuit of commercial supersonic flight an irrational Ahab-like hunt for the impossible, or is it a too-ambitious misadventure in chase of a foolhardy whim that would nevertheless make Icarus proud? Can it be both?

I’m gonna be honest — I never finished Moby Dick. I don’t know how that story ends. I don’t know if Ahab ever got his whale. I don’t know if we will either. But I do know that if we don’t, it won’t be for a lack of trying. Like Icarus, our doom will not come from flying too low and dreaming too small. Our wax wings will not be softened by the ocean’s salty spray, condemning us to a shameful plummet beneath the waves. No — if we fail, it will be because we flew too close to the Sun. We dared too big and failed to contain the sprawling burden of our own ambition.

Remember, Icarus was not a god. He was only human, just like us. Why would we expect him to have acted any differently than he did? And Ahab … probably got his whale? (And was definitely a human — I read far enough to confirm that at least.) Again, I didn’t finish the book, so no spoilers please. But I’m gonna assume that he got the whale, because the general vibe I’ve always gotten from Moby Dick’s cultural imprint is that he eventually killed that whale. And yeah, I’m pretty sure we’ll get ours too.

Concorde is a story of flawed, short-sighted, selfish ascendancy, but a story of ascendancy nonetheless. It shows us that humanity will never stop in its ceaseless pursuit of faster, higher, better. It shows us that we’re not done yet.

Jack Gilbert finishes his poem:

“I believe Icarus was not failing as he fell,

but just coming to the end of his triumph.”

If you enjoyed this piece, consider throwing me a few bucks (I will spend it on snacks).

Further Reading

The Rise and Fall of the Supersonic Concorde – JSTOR Daily

Those who flew the Concorde will miss it – Seattle Post-Intelligencer

An incredibly detailed website about all things Concorde. It has very early Internet vibes and wonderful character.

First-hand account from 9/11 – How Concorde was reborn and died on the same day – Key Aero

The inside story of how BA made more than £500m profit from Concorde – Key Aero

Supersonic flight: will it ever rise out of the ashes of Concorde? – The Guardian

How Concorde Pushed the Limits – Then Pushed Them Too Far – National Geographic

A very thorough breakdown of Flight 4590’s crash by a real pilot.

If you’re curious about the specifics of the science behind this, I highly recommend checking out this video (it’s timestamped to a portion relevant to the above, but the whole thing is fascinating). I was going to take a stab at explaining this myself, but right before I did, I found myself googling “how does flight work” and quickly realized I was out of my depth. Please don’t ask me to explain “vortex lift.”

Given what we know now, this obviously comes across as a bit crass, but I don’t think you can blame the guy for not fully grasping the gravity of what was going on.

I… didn’t even know this existed. I also didn’t know what the sound barrier was. So this was a super fun deep dive.