Whose idea was it to sell ice?

for money i mean

The other day, I was wandering through a street festival when I noticed a young man struggling to carry four large bags of ice.

And when I say struggling, I mean he was struggling. Like, he was trying to carry one of these huge ice bags with his teeth.

I am what you might call “a person who only ascribes himself value when he feels like he is being helpful to others,” so of course I walked up to him and said, “Do you need help carrying those?”

My new friend wordlessly shoved two of the bags of ice into my arms and immediately began walking away from me.

Now, I am nothing if not weak, submissive, and obedient, so of course I dutifully followed him.

We ended up walking three city blocks before we arrived at his destination, which was a food truck where he was working. Take a second to appreciate the fact that he was planning on carrying a ten-pound bag of ice in his naive little mouth for three whole blocks before I stepped in to save the day.

Anyway, it was a very hot day, so during our three blocks of walking, a not-insignificant amount of ice melted all over me and my extremely cute outfit, making it look like I had peed not only my pants but also my shirt, somehow.

And as I was standing there in the street, newly wet and thoroughly debased, I got to wondering, “Where did all this ice come from in the first place?”

Well, I looked into it, and I’m happy to report that the answer involves debtor’s prison, Henry David Thoreau (tangentially), and Norwegian deception. Let’s dive in.

“Where did all this ice come from in the first place?”

Humans have been harvesting ice for a long time.

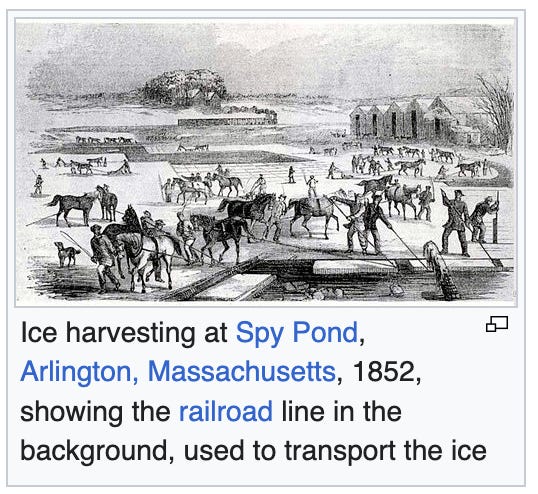

As early as 1780 BCE, people in Mesopotamia were building ice houses to store ice throughout the year. One of the earliest ice houses on record is described on a cuneiform tablet as something “which never before had any king built.”

This ice house, situated on the banks of the Euphrates, was built by a Mesopotamian ruler named Zimri-Lim, whose reign was also marked by being a feminist king, as seen below:

All over the world, people have long been yanking ice down from the slopes of their friendly neighborhood mountains to ensure a consistent ice supply during the hot summer months.

Just like gum, ice is something that humans have been using for free for a very long time, but only relatively recently did someone come up with the idea to sell it (for money).

Okay, everyone say goodbye to the Bronze Age because we’re about to fast-forward to the 19th century and meet the guy who decided frozen water should be a commodity.

The year was 1806 and a privileged 23-year-old from Boston had an idea (not Facebook, too early still). Say hello to Frederic Tudor.

I can’t honestly say that Fred (I’m just gonna call him Fred) is the most likable dude I’ve ever written about (as you’ll soon come to find out) but I really think we all ought to say thank you to Fred anyway.

Why? Because despite his weirdness and his badness, Fred is about to do something that will come to revolutionize food preservation techniques in a way that will change human history. Basically this:

Before Fred came along, New England farmers had been selling blocks of ice from their ponds to wealthy people in nearby cities for a while, but nothing really existed beyond these small local markets.

But here, Fred saw an opportunity. Fred thought to himself, “If rich people in New England love ice, then who’s to say rich people in the American South and the West Indies wouldn’t also love ice?”

Wikipedia tells me that at the time, everyone pretty much thought Fred was either a total freak or a straight-up dumbass – or, as they put it, “at best as something of an eccentric, and at worst a fool” – so Fred coming up with this idea probably seemed par for the course.

But nothing would stop Fred from being convinced of his own genius, and he wanted to act fast:

“Ironically, when [Fred] first came up with the idea of supplying ice to warm weather cities, he was concerned about competitors moving to cash in on his big idea. That concern was alleviated when fellow merchants dismissed him as foolish and crazy.”

Now, “ice as a luxury good for people who had perhaps never in their lives even heard of ice” seemed like an awesome idea on its face, but one big question remained: how do you get the ice down there without melting?

Fred’s first shipment of ice left from Maine for Martinique in February 1806, with the Boston Gazette teasingly reporting, “No joke. A vessel has cleared at the Custom House for Martinique with a cargo of ice. We hope this will not prove a slippery speculation.”

Unfortunately for Fred, things would indeed get a little slippery. His precious ice, insulated with no more than a bit of hay, melted at an estimated rate of 50 pounds per hour during its journey down to the Caribbean.

But despite losing so much ice, Fred still had a decent haul ready to sell when he arrived in Martinique. However, he ran into several more problems here.

First of all, ice was a tough sell to people who were probably seeing ice for the first time in their entire lives. As the BBC puts it, “The residents of Martinique had no interest in his exotic frozen bounty. They simply had no idea what to do with it.”

Furthermore, this very hot and humid tropical island shockingly had zero infrastructure whatsoever that could suitably store ice for extended periods of time, so all the ice that Fred was unable to sell quickly melted.

“Pursued by sheriffs to the very wharf”

Being the determined entrepreneur he was, young Fred refused to let the Martinique melting fiasco cool his business prospects.

Fred had ice depots constructed at his ports of call so his ice could survive the sweltering temperatures that his customers endured. The walls of these early ice houses were insulated with peat and sawdust, and these materials were great for keeping the ice cool, but there was one small problem which was that they were also very flammable, which unsurprisingly did not always go super well for the ice.

But despite the occasional catastrophic fire that destroyed his entire ice supply, Fred’s business steadily improved. Things continued to be volatile for a while as debts piled up, and Fred’s net worth generally charted in the wrong direction, but all in all, Fred did okay.

And of course, by “okay” I mean that Fred only spent a couple of years in debtor’s prison and it only happened one time that Fred was “[p]ursued by sheriffs to the very wharf” before he was able to pull an Assata Shakur (RIP) and flee to Cuba, but apart from those two things, business was booming!

Fred was absolutely cutthroat in the ice game. If anyone tried to challenge Fred’s ironclad hold on the ice market, he simply lowered his prices to one cent per pound, so competitors were forced to either sell their ice at a huge loss while Fred waited for them to go out of business, or simply watch their entire inventory literally melt before their eyes.

Speaking of melting, around this time (1820s and 1830s), ice merchants were losing so much ice to melting that only about 10% of all the ice harvested was eventually sold to anyone. Wastage significantly decreased as the 1800s wore on, but it was an unavoidable part of being in the ice business.

As the ice industry grew and grew, ice became gradually cheaper, which opened up the market to people beyond just the fabulously rich.

Global markets for ice were also starting to materialize. Trade routes opened up to Hong Kong, Sydney, Rio de Janeiro, Kolkata – you name it. Before long, Big Ice had its fingers in everything.

British colonizers in India loved ice so much that they gave ice ships and their cargo special treatment, always making sure they got the best berths in the harbor.

One source notes that in Madras (called Chennai today), ice was included among the goods admitted duty-free, listed just after bullion, coin, precious stones, and pearls.

Fred never stopped innovating in his tireless pursuit of global ice dominance. He eventually figured out that insulating the ice with sawdust slowed down the melting process significantly.

According to the BBC, “Blocks layered on top of each other with sawdust separating them would last almost twice as long as unprotected ice.”

It’s noted that Fred was spending $16,000 a year (around half a million dollars in Today Money) on sawdust alone to insulate the ice during shipment and storage, which really feels like the ice industry equivalent of “Pablo Escobar spent $2,500 a month on rubber bands just to store his cash.”

Fred’s brand new obsession with sawdust worked out really well for everyone, because sawdust was considered a waste product by the lumber industry and they had no other use for it, so everyone was extremely psyched when Fred and all his ice friends suddenly wanted to buy all the sawdust. The 1800s were going so well.

Our guy Fred would eventually come to be known as the “Ice King,” on account of he absolutely tore shit up in the ice industry that he invented all by himself.

Fred did so well selling his “crystal blocks of Yankee coldness” that the Boston Globe found it necessary to clarify that “[Fred] didn’t invent ice.” Thanks guys.

“Ice? yucky” –the British

In their never-ending march to conquer the ice world, the American ice bros decided that their next target would be England.

Now, you might be thinking, “Don’t they already have ice in England? Why would people in (old) England need to buy their ice from (New) England?”

Yes, England had some of its own ice, but thankfully the enterprising American businessmen had a great plan to get British people to buy American ice instead. The Americans told the Brits that their local British ice was dirty and stinky and so, so bad for you, and guess what? The Brits believed them.

I found one source that quoted a “leading ice merchant” as saying British ice had “more gravy in it” but it sounds like they were saying this as a positive thing so idk

Anyway, the American ice invasion of the UK was ultimately unsuccessful mostly because so much ice melted on the boat ride across the pond and also because the Brits simply didn’t care as much about their drinks being cold.

The Brits really just had a complicated relationship with ice. One major ice guy noted that “[ice] appeared to them a strange fish that no one dared to touch” and also wrote this entire paragraph recounting his strange experience watching British people drink water, teasing them about their accents while doing so:

At a given signal the well-trained waiters appeared, laden with the different drinks. The effect was gorgeous, and I expected an ovation that no Yankee had ever had. But, alas! the first sounds that broke the silence were: ‘I say -, aw, waitaw, a little ‘ot wataw, if you please; I prefer it ‘alf ‘n ‘alf.’ I made a dead rush for the door, next day settled my bills in London, took the train for Liverpool and the steamer for Boston, and counted up a clear loss of $1,200.

Back in the U.S., the ice market continued growing with no signs of slowing down as people kept finding fun new ways to use ice to improve their lives.

What did they use the ice for? Here are a few favorite examples:

Keeping drinks cold (water, milk, newly popular cocktails like the mint julep)

Preserving food

Making ice cream!

Inventing refrigerator cars for trains

I like this last one especially, because some of the earliest refrigerator cars were incredibly rudimentary. Like, they just hucked 3,000 pounds of ice into a boxcar and piled tons and tons of meat on top, which, in case you weren’t sure, was not great for the meat.

After spending hours in direct contact with the ice, the meat became discolored and tasted very bad. If you’d like to recreate this at home, try wrapping a piece of lunch meat around an ice cube and see what happens.

(Seriously, please try this and let me know what happens. I’m aiming to be the most important scientist of my generation and this is a crucial first step. The entire Norwegian Nobel Committee is subscribed to my Substack and reading these words right now.)

Anyway, the ice business continued being extremely popular and trendy as the 1850s arrived. People wanted ice really bad and they weren’t gonna stop wanting ice literally ever.

Ice companies were desperate to find more places to get ice. They even started taking ice from Walden Pond, about three years before Henry David Thoreau showed up and started thinking about stuff.

As the country grew westward and Americans settled in places like California, ice merchants needed to start figuring out how to get ice to them.

Ships full of ice were sent all the way down and around South America so people in San Francisco could have their sweet sweet ice. But then all the east coast ice bros were like “this is way too expensive” so San Francisco had to buy their ice from Russian-controlled Alaska instead.

To give you an idea of how lucrative the ice trade was, the Russians created an entire lumber industry in Alaska just so they could take the sawdust from the sawmills to insulate the ice in transit. And a few decades later when the Russian ice trade collapsed, all these Alaskan sawmills went out of business, too, so dependent were they on the ice companies buying their sawdust.

“Congealed Water”

In an effort to meet the insatiable demand for ice, some people started thinking about how to make ice artificially rather than harvesting it from ponds.

However, artificial ice technology was still in its infancy, so this effort didn’t go super well for a few reasons:

Required a lot of fuel

Required a lot of money

Sometimes ammonia got into the ice (bad)

Sometimes the ice plants exploded (also bad)

For now, pretty much the only place where artificial ice could compete with natural ice was Australia, and that was because it took almost four months to ship ice from New England to Australia, during which over a third of the ice melted.

Over in Europe, the Norwegians decided it was time to get in on this ice nonsense, and they had a very sneaky plan to do so.

There was a successful American ice dealer called the Wenham Lake Ice Company, and the Norwegians, being the sneaky sneaky snakes they were, wanted to mooch off their success.

So, they simply renamed one of their lakes, Lake Oppegård, to “Wenham Lake” to trick British people into buying their ice instead. And guess what? It worked.

Apparently, the people of Britain had gotten over their earlier revulsion to ice, because they were absolutely obsessed with this Wenham Lake stuff (presumably the real stuff more so than the counterfeit Norwegian bastard ice).

Wenham Lake ice was claimed to be “so clear and transparent a newspaper could be read through a block two feet thick.”

Wenham Lake ice was “so rapidly advancing in popularity in the metropolis that no banquet of any magnitude is considered complete without it.”

Everyone loved this stuff. In London, “hotels put up signs informing their customers that Wenham Lake ice was served there,” and it was even said that Queen Victoria “insisted that it always be made available to her.”

Okay, picture this: the year is 1879. Ice is so hot right now. We’re talking “the country’s second-largest export … following only cotton” hot.

Back in the big eastern cities of the U.S., households are consuming over 1,300 pounds (over 600 kg) of ice every year. Ice companies need 1,500 wagons to deliver ice in New York City alone.

But you know what else is so hot right now? The temperature, because of that one time humans did the Industrial Revolution and everyone started blasting whatever the hell they wanted into the atmosphere. Oops!

The planet was warming way the hell up which was making it harder for water to freeze in the winter, which, as you probably could have guessed, was not an awesome development for the ice companies.

At this point in the story, we get to learn about the term “ice famine,” which was when a city ran out of ice during the summer and everybody freaked out. Ice famines are about to start happening all the time.

Ice famines usually occurred when the winter was unseasonably warm and ice companies simply couldn’t amass enough stock to serve their customers for the rest of the year.

Supply chain issues were also a huge culprit – trains transporting ice had a harder time stopping the ice from melting en route to its destination when, as The New York Times put it, “[a]ll day the weather acted in a freaky way.”

Ice famines drove ice prices up which was great for the ice companies but bad for everyone else. In particular, it was bad for poor people – a 1907 report from The San Francisco Call predicted, “[t]he poor people probably will have a disastrous summer.”

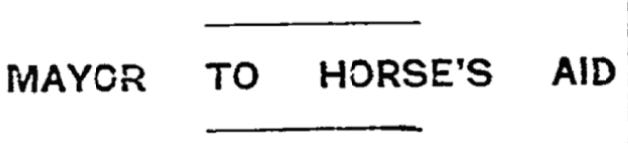

It was also bad for horses, dozens of whom succumbed to the heat during a 1911 heat wave in New York City. This was unequivocally a Very Upsetting Occurrence but the silver lining is that we got this certified Very Funny Headline from the NYT:

What do the Amish and World War I have in common?

As the 19th century came to a close, the technology to produce artificial ice was finally becoming good enough that it could compete with natural ice.

People were also drawn to artificial ice because they were afraid that natural ice was dirty and contained yucky germs (e.g., industrial pollutants, typhoid), which was probably right.

With artificial ice surging, natural ice companies started to panic. Some of them developed new and improved ice harvesting tools to increase efficiency, or they invested in artificial ice themselves.

Others opted for trickery (awesome) and tried to convince everyone that natural ice melted more slowly than artificial ice (lie, simply not how ice works).

Others opted for even less ethical tactics, by which I mean “exploiting their monopolies and price gouging everyone during heat waves.”

People were understandably extremely pissed about this. One ice titan in New York tripled his prices during a 1900 heat wave, a crime for which his punishment was being sent to prison facing zero consequences and profiting over a quarter of a billion dollars (adjusted for inflation).

By the time the U.S. entered World War I, the ice industry was on its way out. But weirdly enough, the war was actually fantastic for the ice business, and natural ice in particular.

During the war, chilled food shipments from the U.S. to Europe skyrocketed, which placed a huge burden on American refrigeration facilities that needed to keep this food cool before it was sent overseas. Natural ice was used to successfully alleviate this burden.

Additionally, the ammonia and coal that were needed to keep refrigeration plants running were in short supply due to the war effort, giving natural ice another boost.

In short, World War I was terrible for everybody except dudes with ponds in New England. If you were a dude with a cold, cold pond you were having a great time while everyone else was being slaughtered.

After the war, the ice industry slowly disappeared. Or melted, if you prefer.

Cooling technology got progressively better and cheaper, so refrigerators became more common in businesses and homes. Nobody needed to call the iceman anymore.

Today, this industry that was once among the largest in the U.S. basically no longer exists. It’s kept alive by people who make ice sculptures and ice castles and other miscellaneous large-scale ice projects, but beyond that, no one really has a pressing need for huge blocks of ice anymore.

…unless you’re Amish! Yeah, the Amish still buy ice.

In Ohio, “Amish make ice a hot commodity,” and in Pennsylvania, the iceman is a very sexy dude that all the Facebook commenters are extremely horny for. Some favorite comments:

“if that was the ice man in my area I’d rip the electrics outta my chest freezer too!!”

“I think I might need ice…”

“I’d probably let him fill my ice box;)”

Outside of Amish country, we still see ice harvesting touted as a tourist attraction, such as the New Hampshire “ice wranglers” who cut up the ice, “much to the delight of many visitors, especially when their age is in single digits.”

Additionally, some people keep carving ice for the sake of tradition, like these folks in Maine.

But save for those select few examples, the ice trade is a thing of the past, with almost nothing remaining in the world today to remind us that it even existed in the first place.

I love learning about things like this because it gives me a glimpse into a world that is wholly unrecognizable from a modern perspective. The way humans lived back then is so different from today that it may as well be an alternate universe, but of course, it’s all a part of our story. It’s all a part of who we are as a species and as members of a collective culture.

Sharing and celebrating knowledge like this is a way of keeping these stories alive. We honor the people who came before us and whose existence enabled our own existence by appreciating (and making fun of) all the ways they lived, and in doing so, we give life to these memories that no amount of ice could possibly preserve.

Thanks for joining me on yet another adventure through the rabbit hole, in all its unexpected twists and turns. I hope I’ve given you some new perspective and appreciation for the rather mundane miracle of widespread access to ice, and the next time you order ice in your beverage, you think about the bizarre and circuitous journey through history it had to take to arrive in your cup. Until next time.

If you enjoyed this piece, consider tossing me a few bucks (I will spend it on snacks)

Love history. Love history stories most of all. I'm sure battles and dates and famous people have value but they do lack the human element of pure story-telling. Maybe if the Battle of Waterloo started out "Once upon a time..." a lot more people would read about it.

I like this