With the death of Pope Francis, the world turns once again to the storied and secretive tradition that is the papal conclave. In the next few weeks, the cardinals will gather in Rome, hole up at the Sistine Chapel, and eventually emerge to declare “habemus papam” (we have a pope).

It is the world’s oldest surviving historical method for electing a head of state and its procedures have been continuously developed for nearly two thousand years. The roots of the conclave process are hidden in its name — the Latin con and clavis combine to form “with a key,” on account of their being locked up and all.

But why did they start locking up the cardinals? Is it because the cardinals proved they couldn’t behave? The answer, as it turns out — and this is true — is yes.

Let’s take a field trip back to 1268. It’s a leap year — fun. Hungary is at war with Bulgaria — not fun. France just decided that it’s illegal to make beer out of anything except for malt and hops — okay. Oh, and the pope just died. Pope Clement IV, to be exact — born Gui Foucois (Guy Foulques), he was also called Guy le Gros (Guy the Fat), or, in Italian, Guido il Grosso (seriously).

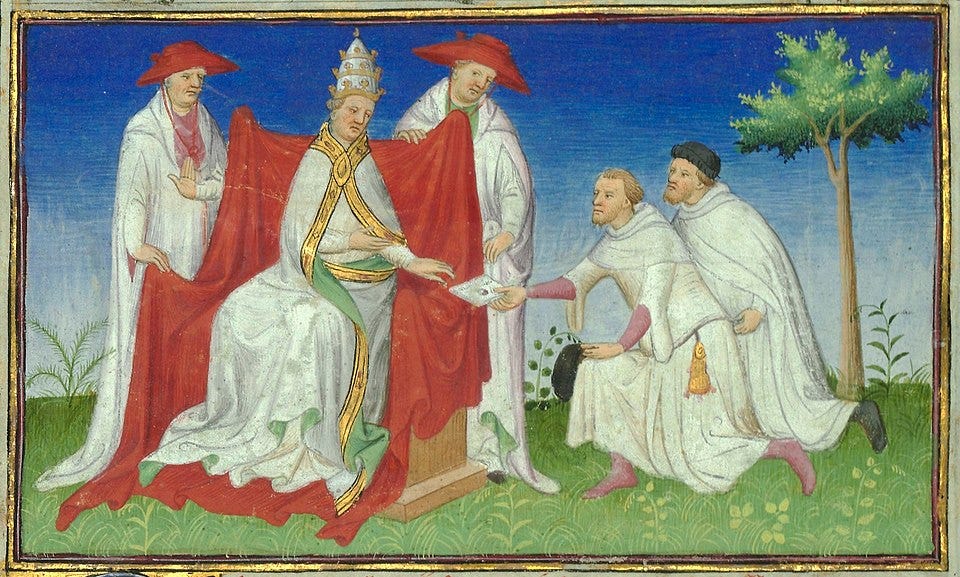

Clement’s papacy came at a time of intense division within the Church, and that division would come to boil over during the papal election following his death. The cardinals gathered to vote in Viterbo, about 40 miles northwest of Rome, as tradition dictated that the election be held in the city where the previous pope died. Other popes elected in Viterbo include John XXI, who died at his papal palace after the ceiling of his recently-build study collapsed on him while he slept. Good times.

The election began with the cardinals meeting to vote once a day, which carried on for several months. We don’t know for sure how many candidates were considered, but historians think that at least six of the nineteen cardinals in attendance were in the running at one point or another.

After many months of meetings and no new pope, the cardinals were deadlocked. Frustrated by this lack of progress, the magistrates of Viterbo (the guys in charge) decided to round up all the cardinals and sequester them in the Palazzo dei Papi until a new pope was chosen. Up to this point, cardinals had been free to return to their residences after meetings concluded, but that was no more. It was compulsory sleepover time.

But alas, even being forced to stay under the same roof could not compel the cardinals to a compromise. So, the magistrates of Viterbo, in all their infinite wisdom, decided that the most natural next step to encourage a quick result was to … do you want to guess? You should guess. I really think you should guess. But I also think you will never in a million years guess what they did next.

They took away the roof.

Yes, the roof. The whole entire roof. One account says an English cardinal first suggested the roof be removed, saying, "Let us uncover the Room, else the Holy Ghost will never get at us.”

Can’t argue with that logic. In addition to losing the roof, the cardinals’ rations were reduced to bread and water.

Unsurprisingly, the cardinals were not huge fans of this whole “no roof” thing. Some sources say they threatened to put the entire city of Viterbo under an interdict, leading to the assembly of a makeshift roof.

Quick aside: An interdict is basically a censure from the Church that temporarily prohibits certain religious activities, like holding church services or taking the sacrament. Interdicts have been issued against individual persons, whole cities, and even entire kingdoms. My favorite interdict was when Pope Innocent III put the entire Kingdom of France under interdict to force Philip II to take back his second wife, Ingeborg of Denmark (long story).

Anyway, the roof. They took away the roof, and the cardinals were not pleased about it, but it was a clear signal to them that it was time to hurry things along. The cardinals created a committee of six representatives among themselves and empowered the committee to choose a new pope. Still, though, they could not decide on a candidate from among their ranks to assume the papacy.

Now, while we generally assume that the pope has to first be a cardinal in order to be elected, just like we assume a Supreme Court justice has to first be a judge in order to be nominated, neither are true. (See: Harriet Miers.) Technically, any baptized Roman Catholic male is eligible for the papacy, and it was this “technically,” after nearly three years of sede vacante, and after the death or resignation of four of the twenty electors, that led to the election of one Teobaldo Visconti.

If this news came as a surprise to the Church’s followers, they were not alone — Teobaldo himself was just as shocked as anyone. See, when the news reached him, he was actively participating in the Ninth Crusade at Acre with England’s King Edward I. He was not even a member of the priesthood and had to be ordained and consecrated a bishop before his coronation as pope.

Teobaldo was crowned on March 27, 1272 in St. Peter’s Basilica, taking the papal name Gregory X. Perhaps his greatest accomplishment as pope was the establishment of new rules guiding the election of future popes, rules which form the basis of the conclave’s laws today.

With his papal bull Ubi periculum, Gregory aimed to prevent future fiascos like the one that led to his selection as Primate of Italy and to ensure greater stability within the Church. As is traditional with papal bulls, Ubi periculum’s title is taken from the opening words of its original Latin text, “Ubi periculum maius intenditur,” or “Where greater danger lies.”

Ubi periculum’s rules were first put into practice for the January 1276 election of Innocent V. Though 184 popes had come before, this election is considered the first conclave. Cardinals were secluded and barred from outside contact, not even being given separate rooms for the duration of their proceedings. (If the film Conclave is to be believed, this last part has since changed.)

All meals were passed through a small opening. If a new pope had not been elected after three days, their daily rations were reduced to a single meal. If no decision had been made after eight days, cardinals would be given only bread and water (and a little wine, as a treat). Ubi periculum contains no guidance as to the disciplinary raising of the roof.

Importantly for certain someones with a stake in papal elections not dragging on forever (looking at you, magistrates of Viterbo), enforcement of these rules was left up to the officials of the city hosting the conclave, but they were not permitted to simply ad-lib their own additional rules (i.e. roof).

So, were these reforms effective? You bet they were. Innocent V’s election only took one day, and when he died five months later, only nine days were needed to choose Adrian V. However, the cardinals weren’t fans of the new rules. Perhaps the two days of bread and water they’d had to endure set them off, and they convinced Adrian to suspend the rules on day two of his papacy.

But not to worry — Adrian insisted that he would, essentially, “repeal and replace” Ubi periculum with newer, better rules, and proceeded to die shortly thereafter, only 38 days into his papacy, before he’d even been ordained as a priest, without having instituted new rules governing papal elections.

You might be thinking, “That sounds bad.” You might also be thinking, “Hey, that’s two pope deaths in a really short time period.” Indeed.

If you’ve been following along on your calendar, you may have realized that Adrian V was the third pope of the year in 1276. Three whole popes in one year! That’s a lot of popes! Has that ever happened before?

Oh, you know it.

There have been thirteen years of three popes throughout history, most recently in 1978. History has seen more years of three popes than New York Jets playoff wins.

Adrian’s only act as pope had been to suspend Ubi periculum, so when the cardinals gathered again in Viterbo, it was without the rules that had previously guided them. There were two main factions — the French and the Italians — and neither had sufficient votes to elect their own candidate.

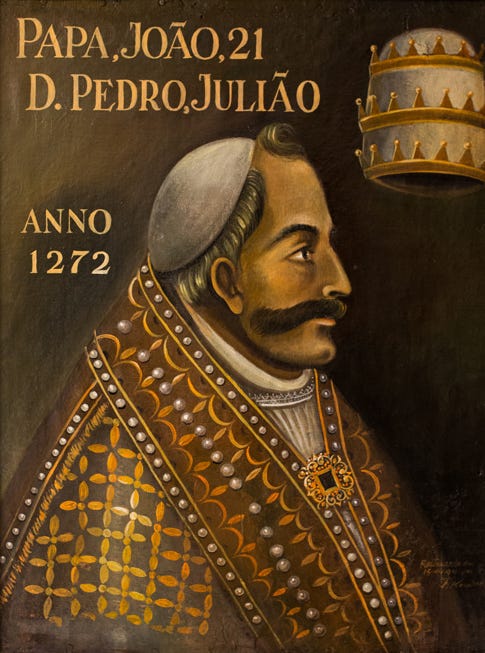

In a compromise, they selected the only neutral cardinal, Pedro Julião, who became the only ethnically Portuguese pope in history. Pedro selected John XXI as his papal name, and his September 8th coronation made 1276 the Year of Four Popes, the only such occurrence in the history of the Catholic Church.

John studied medicine as a young man, and some historians believe he was the only pope to have been a physician. These interests persisted into his papacy, and to ensure he had a quiet environment in which to work, John had an apartment added to the papal palace.

You may recall from earlier the pope who died when his study’s ceiling collapsed on him in his sleep. Yeah, this is that guy again. John actually survived the initial collapse after being unburied from the rubble, but he would succumb to his injuries less than a week later.

John is also remembered for that time when he got confused about how many Pope Johns there had been before him, so he took the papal name John XXI despite there having never been a John XX. A real “papal iPhone 9“ situation if you ask me. John’s blunder helped give birth to one of my favorite Wikipedia article titles of all time, and for that, I am grateful.

John formally reversed Ubi periculum after Adrian suspended it, and the following five papal elections reflected that lack of rules, with an average papal vacancy of nearly ten months.

The 1277 election followed a familiar blueprint — months of deadlock along national lines, the magistrates of Viterbo getting sick of it and locking the cardinals inside the palace, and a new pope being elected shortly thereafter (Nicholas III). This election also has the distinction of being the smallest in the Church’s history, with only seven cardinal electors participating. Compare that to the 135 cardinals eligible to vote as of April 2025 (out of a total 252 cardinals, among whom those older than 80 are no longer eligible).

The next election lasted exactly five months and saw the magistrates of Viterbo violently remove two cardinals who were accused of impeding the process, which, honestly, can you blame them? You could not pay me enough to be a magistrate of Viterbo, goodness gracious. One of the cardinals blamed the disruption on the people of Viterbo, who he claimed had a history of unruliness and disrespect for the Church, which, again, is totally understandable given the circumstances.

The papacy’s approval ratings in Viterbo must have been in the toilet, or the chamber pot, or whatever. Anyway, the removal of the two cardinals (both Roman) cleared the way for the French faction to elect one of their own, which is how we got Martin IV. And the entire city of Viterbo, for its apparent unruliness, earned itself a good ol’ interdict (you remember those, right?).

The 1285 election stands out for its (relative) normalcy amidst all this chaos. Perhaps because they began meeting on what would eventually become April Fools Day, or perhaps for some other reason, the very first ballot saw the cardinals unanimously elect Giacomo Savelli to become pope. The 75 year-old cardinal was an odd choice for the papacy, given his severe arthritis and the difficulty he had getting around.

Pope Honorius IV, as he was now known, could barely stand or walk, even with crutches, and had to have a chair designed specially for him so that he could be seated at the altar during Mass. His Holiness also had to have his arm mechanically supported so he could raise the host, which is when the priest lifts up the Blood and Body of Christ (bread and wine) after consecrating them to show the congregation. At the raising of the host, the priest echoes the words of Jesus at the Last Supper by reciting 1 Corinthians 11:24, which reads, “This is my body, which is broken for you,” and I think Honorius meant that literally.

Brief summary of Honorius’s papacy:

interdicted Sicily for reasons we won’t get into right now

excommunicated the king of Sicily for reasons we won’’t get into right now

passed 45 ordinances largely aimed at protecting the people of Sicily from their king, for reasons we won’t get into right now

OK, moving on.

Sixteen men walked into Rome’s Santa Sabina on April 4, 1287, and only seven walked out when they emerged with a new pope ten and a half months later. (Six died, three left Rome and never returned.) One-third of the College of Cardinals was wiped out during the deadliest papal election in history. It’s thought that the cardinals perished of malaria. Following the deaths, the surviving cardinals left Rome for several months to wait out the disease, and upon their return, they found that Cardinal Girolamo Masci had remained at the basilica the entire time, working to purify the air and eradicate it of disease.

Of course, this was back when people thought that all manner of disease, from malaria and chlamydia to cholera and the Black Death, were caused by a “miasma,” or bad air. Malaria is literally mal + aria — Latin for bad air — and was formerly called “marsh fever” due to its association with swamps and marshland. Hey, at least they were on the right track, you know? They figured out it had something to do with swamps. Points for trying.

So, thanks to this theory of disease first advanced by Hippocrates (of Hippocratic Oath fame) in the 4th century BCE, Cardinal Masci stayed behind in Rome tending a fire that “purified” the plague-ridden mal aria in the basilica, at what was thought to be great risk to himself.

Prior to their departure from Rome, the cardinals had been hopelessly divided, so when they discovered Masci and his incredible sacrifice, they immediately elected him pope. Masci, though, was extremely reluctant to accept their decision, and in fact, did refuse to accept for an entire week. It wasn’t until they’d elected him a second time that Masci would accept his ascendancy to the papal throne, choosing the name Nicholas IV in honor of Pope Nicholas III, who had made him a cardinal.

Nicholas was the first Franciscan to be made pope, and he was consequential in several different ways. A year into his papacy, Nicholas issued a decree that granted half of all the income earned by the Holy See to the cardinals, and allowed them a share in the financial management of the Church. This decision paved the way for the growing independence of the College of Cardinals and increased the extent to which they could be a thorn in the pope’s side.

Nicholas also worked to spread the Church’s influence around the globe, sending the Franciscan missionary Giovanni da Montecorvino to Kublai Khan’s court. Montecorvino established China’s first Roman Catholic church in 1294, as well as its second in 1305. He learned the local language, preached in it, and translated the New Testament and the Psalms into Uyghur. It’s estimated that he converted between 6,000 and 30,000 people to Catholicism by the year 1300, and Franciscan tradition even maintains that he baptized the third Yuan monarch, Külüg Khan, but this is disputed.

Montecorvino is also said to have purchased about 150 boys aged 7 to 11 from “heathen” parents. He instructed the boys in Latin and Greek, wrote psalms and hymns for them, and trained them to serve Mass and sing in the choir.

Giovanni da Montecorvino died in 1328 in what is today Beijing. By 1369, all Christians were expelled from China by the Ming Dynasty.

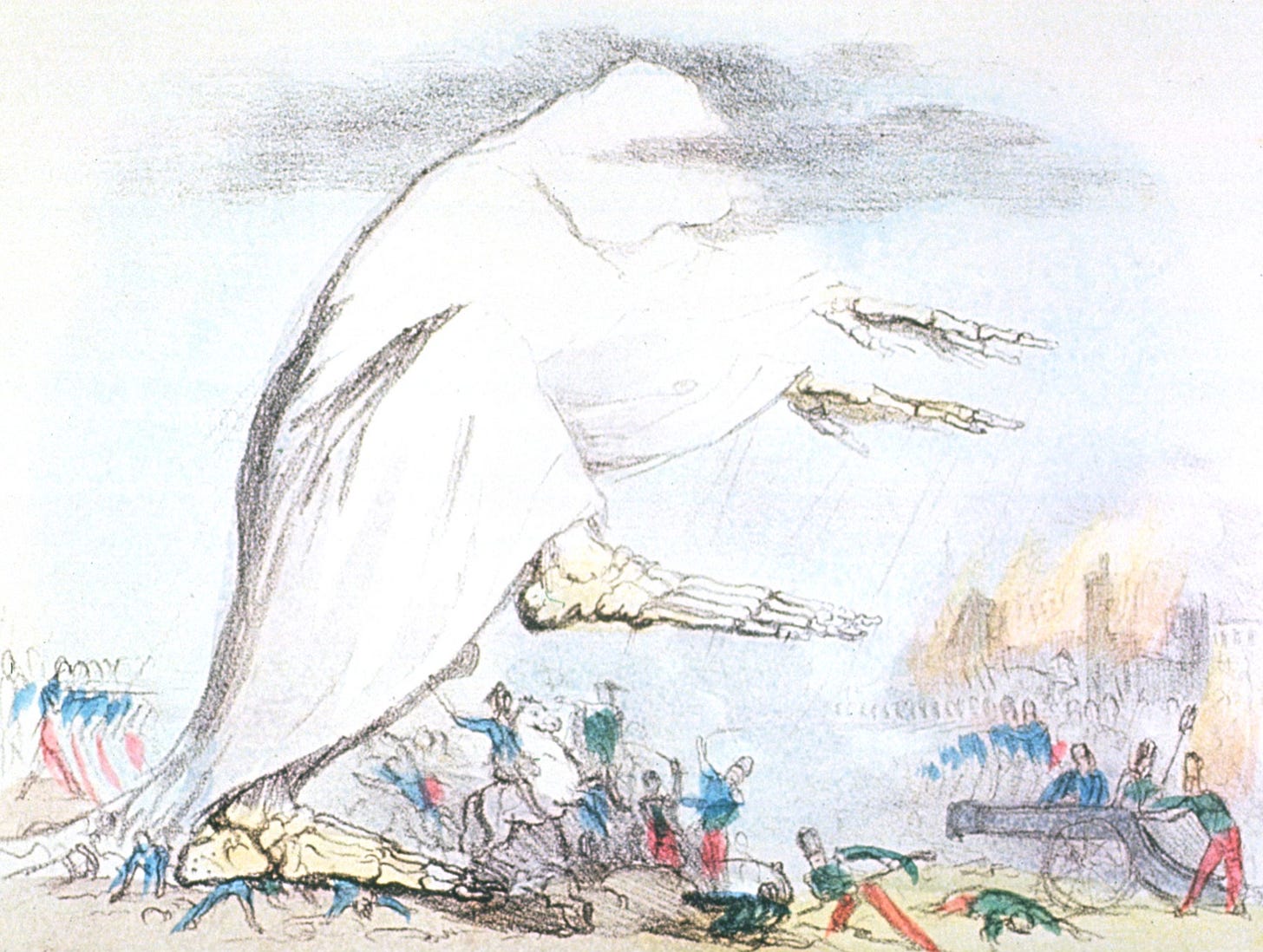

After Nicholas’s April 1292 death, the cardinals gathered in Rome for what would be the last papal election that did not take the form of a conclave. Ten days of fruitless voting were followed by an adjournment of two months, and when an epidemic struck the city, killing the French cardinal Jean Cholet, they recessed again until September. Voting dragged on through the fall, winter, and spring, continuing all the way into the subsequent summer, with disorder rising in Rome all the while. Angered citizens destroyed palaces, killed pilgrims, and plundered churches, driving the cardinals to decamp for Perugia and reconvene in October.

Deliberations were no more productive in Perugia, a hilltop city halfway between Florence and Rome. Another year passed without result, and in the summer of 1294, beleaguered cardinals began to disperse. Just six cardinals remained in Perugia for what would be their final meeting, where a letter was read aloud from the revered hermit Pietro Angelerio.

In his letter, Angelerio decried the cardinals’ persistent inaction, warning that God had revealed to him an imminent punishment that awaited the cardinals should there be any further delay. Sufficiently scared straight, the senior-most cardinal present immediately nominated Angelerio for the papacy. The wildcard candidate was quickly agreed to by the rest of the electors, and the contest was thus concluded.

Shortly thereafter, a small party ascended to Angelerio’s mountaintop hermitage, where the illiterate octogenarian slept on a bare rock inside a cave. Following the example set by John the Baptist, Angelerio lived as a strict ascetic, fasting every day of the week except Sunday and observing Lent not once, not twice, not thrice, but quadrice four times throughout the year, passing three of them on bread and water alone. Angelerio also practiced mortification of the flesh, whose adherents seek to destroy their sinful nature by using pain and discomfort to distract their minds from temptation. By sharing in the suffering of Jesus, it is thought, they sanctify themselves.

Instruments of penance include, but are not limited to:

The discipline, a small seven-corded whip used to self-flagellate one’s back.

The hairshirt, which is exactly what it sounds like — a garment made from camel’s hair, designed to irritate the skin, sometimes further adorned with thin wires or twigs to amp up the discomfort even more.

Iron girdle.

Romans 8:13, considered a precursor to Christian ideals of self-mortification, reads:

For if ye live after the flesh, ye shall die: but if ye through the Spirit do mortify the deeds of the body, ye shall live.

Also relevant is Zechariah 13:6:

And if anyone asks them, “What are these wounds on your chest?” the answer will be “The wounds I received in the house of my friends.”

And last but certainly not least, 1 Kings 18:28–29:

Then they cried aloud and, as was their custom, they cut themselves with swords and lances until the blood gushed out over them. As midday passed, they raved on until the time of the offering of the oblation, but there was no voice, no answer, and no response.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the humble Angelerio refused to accept his election as pope, and according to the contemporary historian Petrarch, he even tried to flee upon being informed. Eventually, though, he relented, but the stubbornness did not stop there. Instead of accompanying the cardinals back to Perugia to accept the papacy at the site of his election, as was tradition, Angelerio insisted that they come to him in nearby L’Aquila for the coronation.

The cardinals agreed, and they proceeded with his coronation at L’Aquila’s basilica, Santa Maria di Collemaggio. Angelerio had a special connection to this church — while traveling through L’Aquila in 1274, he spent the night on a nearby hill (the Colle di Maggio) and dreamt a vision of the Virgin Mary, who was surrounded by angels at the top of a golden stairway. Santa Maria asked Angelerio to build a church there in her honor, and Angelerio obliged.

Angelerio rode through L’Aquila on a donkey, imitating the entry of Christ into Jerusalem, as he made his way to the church. He received his crown and took the name Celestine V. However, only three cardinals were present for this ceremony, so when the remaining cardinals arrived into town a few days later, all the pomp and circumstance was repeated, making Celestine the only pope to receive two papal coronations. Historical sources say enormous crowds were present to witness the coronation(s), with up to 200,000 attendees including kings and princes from all over Europe, as well as the preeminent poet Dante Alighieri.

One month after being consecrated pope, Celestine issued a papal bull that pardoned the sins of all those who visited the church to confess and repent on the anniversary of his coronation. Still celebrated today as the “Celestinian Forgiveness,” it is widely viewed by church historians as the direct predecessor to the Catholic Jubilee, instituted only six years later by Pope Boniface VIII. Historically, Jubilees are special years of remission, in which sins and debts are forgiven and differences are reconciled.

Celestine’s “Bull of Forgiveness,” as it was known, was exceptional in its openness to all devotees of the Church, including the poor and the marginalized. Prior to this, such forgiveness had only been granted to crusaders departing for the Holy Land and pilgrims to the Porziuncola in Assisi, which was largely only accessible to the wealthy.

Now in its 731st year, the Celestinian Forgiveness still draws large crowds to L’Aquila during the waning days of August. Beginning on the afternoon of August 28, a procession departs from the town hall, with participants clad in traditional costumes, and winds its way through the town streets. They are brought up in the rear by the Lady of the Bull, a young woman carrying the original papal bull with which Celestine has absolved countless sinners. As the sun draws nearer to the western horizon, the procession arrives at Santa Maria di Collemaggio, where a cardinal specially designated by the Vatican opens the Porta Sancta, or Holy Door. All through the night and into the next day, a stream of pilgrims will arrive at the basilica built by Celestine himself, entering through the Holy Door to seek salvation from their maker. After the sun sets on the evening of August 29, the Holy Door is shut and will not be opened again for another year.

In 2022, Pope Francis traveled to L’Aquila and became the first pontiff to open the Holy Door in 728 years. Before following the centuries-old tradition of knocking thrice upon the Holy Door with an olive wood staff, Francis offered the following prayer:

“Holy Father, … deign to respond to our hopes: open completely to us the doors of your mercy, so that one day the doors of your heavenly dwelling may be open to us … that we might all together sing to you forever. Grant, we pray, that all those who cross this threshold with renewed commitment and firm faith might obtain salvation which comes forth from you and leads us to you.”

After issuing his Bull of Forgiveness, the remainder of the papacy would unfurl quickly and lamentably for Celestine. One Catholic encyclopedia remarks, “It is wonderful how many serious mistakes the simple old man crowded into five short months.” Celestine realized he was not cut out for the intense demands of papal life and desired a return to his hermitage, even apparently having had a replica built in one of the rooms of his papal palace.

Cardinals began to agitate for Celestine’s resignation, and it was not long before he published a decree establishing the right of popes to abdicate the throne. The document was drafted by Cardinal Benedetto Caetani, who immediately succeeded Celestine as pope. Caetani’s legal guidance sought to address the question of whether the pope was even allowed to resign at all. There was uncertainty as to who could be empowered to accept the pope’s resignation, as his position as the head of the Church and the ruler of all its earthly domains was outranked only by God himself.

One week later, Celestine resigned, stating a desire to return to the life he’d left behind when he donned the papal robes. Besides his edict creating the right of papal resignation, nearly all of Celestine’s other official acts were annulled by his successor, Boniface VIII.

However, before he gave up the throne, Celestine did make one more important change that continues to impact the proceedings of the Church to this day. In three separate papal bulls, including one issued just three days before his resignation, Celestine officially re-enacted Gregory X’s Ubi periculum after two decades of its status being in flux. Ubi periculum has governed all subsequent papal elections under the strict rules of the conclave.

The next election, in 1294, saw Boniface VIII elected on the first scrutiny, ascending to the throne on Christmas Eve. Then, after Boniface’s 1303 death, Niccolò Boccasini was unanimously elected — again on the first scrutiny — becoming Pope Benedict XI. Benedict thoroughly documented the conclave that elected him and noted how it followed Ubi periculum’s mandated procedures precisely.

The conclaves that have transpired since have certainly not been without incident — far from it — but they have been guided by a common tradition passed down through ages, carefully designed to keep the Church stable and intact. Beyond the primary goals of limiting distractions and outside influence, the strict rules imposing an essentially monastic lifestyle within the conclave’s walls may have also been intended to unshackle the cardinals from the day-to-day concerns of church governance, and instead focus their minds fully on the eminently important task at hand of electing a new pope.

The conclave that elected Pope Francis took only around 24 hours, electing him on the fifth ballot. Before that, Pope Benedict XVI’s election only needed four ballots across two days. John Paul II — eight ballots in two days. John Paul I — four ballots in two days. It continues like that as you stretch back through history, and you’d have to go all the way back to the 1830-31 conclave that elected Gregory XVI to find a conclave that lasted longer than a week (83 ballots in 50 days). No conclave since has exceeded five days or fourteen ballots.

Today’s Catholic Church is in a markedly steadier state than the version of itself that has existed in centuries past. Popes no longer have to worry about being murdered in dungeons or banished to monasteries. Cardinals at this next conclave will almost certainly not be arrested by the magistrates of Viterbo. If anything is to fall upon Rome while the electors are convened, it will surely be rain rather than an interdict.

But that is not to say that the Church is on entirely steady footing. To be sure, it faces a deluge of problems that can and should force the cardinals to reckon with the best path forward for the institution. To name a few:

Thousands of members of the clergy have been accused of sexual abuse against children, some as young as three years old. Many allegations detail decades of abuse. Rather than expelling predators from the Church’s ranks, officials have instead engaged in systematic coverups, sweeping allegations under the rug and shuffling priests around to make accusations disappear. And this is seemingly nothing new for the Church — Martin Luther claimed in 1531 that Pope Leo X had vetoed a measure to restrict the number of boys that cardinals kept for their pleasure, “otherwise it would have been spread throughout the world how openly and shamelessly the Pope and the cardinals in Rome practice sodomy."

The Church has struggled with declining membership as social values and spiritual priorities have shifted. Weekly church attendance among Catholics in the U.S. has fallen from 45% in the early 2000s to 33% in recent years. The share of U.S. adults who identify as Christian has been steadily declining for years (although recent findings show this decline may be steadying or even reversing, and declines among Catholics in particular are more modest). Young adults are even less likely to identify as Catholic, and are just about as likely to be religiously unaffiliated (atheist, agnostic, etc.), which does not bode well for the Church’s long-term strength.

Despite growing societal acceptance of LGBTQ+ rights, the Church still maintains that marriage is between a man and a woman and that gay sex is a sin. Francis was significantly more welcoming of the LGBTQ+ community than any of his predecessors — as exemplified by his famous, characteristically casual “Who am I to judge?” press conference early in his papacy — but there is still a long, long way to go. This is still the same pope who met with Kim Davis shortly after her release from jail (the Vatican said the meeting was not an endorsement).

This next election will not have the same internal divisions, external pressures, or existential stakes as the 13th-century elections that inspired the rules which will guide it, but the task before the cardinals is no less daunting. 2025 is no 1268, but the Church arrives at a crossroads nonetheless. As the cardinals gather in the Sistine Chapel to select the inheritor of the papal throne, the 266th apostolic successor to Saint Peter himself, they will be charged with deciding upon not just the next pope, but the future of the Church as a whole.

“I call as my witness Christ the Lord who will be my judge, that my vote is given to the one who before God I think should be elected.”

Each cardinal will recite these words as they cast their ballots, neatly folded twice, marked with the name of their chosen candidate, and written in a way that won’t allow them to be identified by their handwriting. One by one, in order of seniority, cardinals will rise from their seats to approach Michelangelo’s fresco The Last Judgment and make their decision before God. And they will continue voting, folding, rising, approaching, reciting, one by one, until a two-thirds majority has formed behind one of the cardinals and he accepts his election as pope.

Only then will the white smoke rise and will the Vatican bells ring out in celebration of a new supreme pontiff. Only then can it be declared once more: Habemus papam.

Let’s just hope they can keep the roof on the place.